Italy’s Dual Economy Is Holding It Back (I)

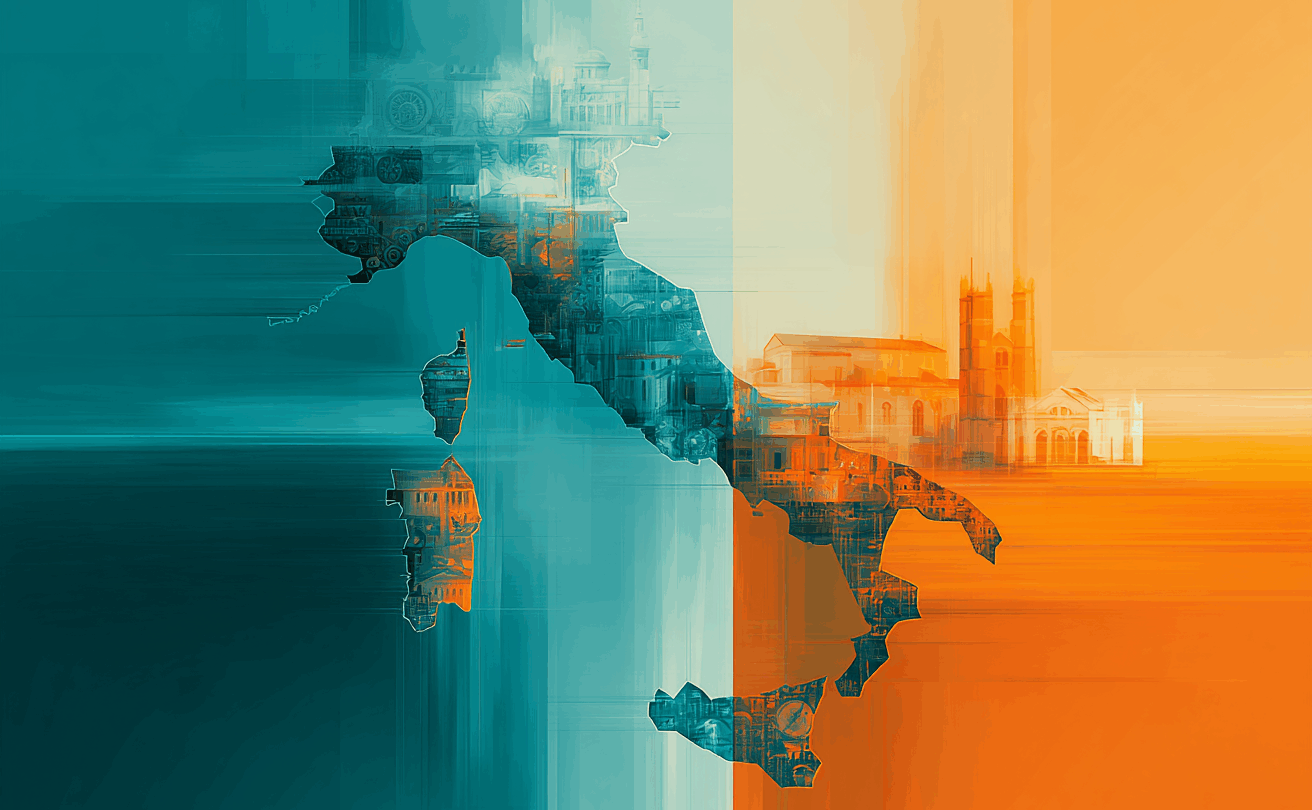

Closing Italy’s North–South divide is key to any growth strategy.

Executive Summary

Italy’s growth model remains puzzling to academics and policymakers. It doesn’t fit neatly into classic categories of coordinated or liberal capitalism. Nor does it operate as a coherent national growth regime. This paper argues that to understand Italy’s economy, we must look below the national level — at regional growth regimes that diverge sharply in structure, drivers, and institutional support.

Italy is not one, but two economies. In the north, a manufacturing-based, export-led regime dominates. It is supported by dense industrial districts, skilled labour, and competitiveness-enhancing territorial institutions. Growth in these regions is driven by global integration and productive investment. In the south, by contrast, a state-dependent regime prevails. Here, growth and employment rely on the public sector — via public employment, social transfers, and lenient enforcement of tax and labour rules. The authors call this model “administrative Keynesianism.”

This dualism is not just a legacy of underdevelopment — it is actively reproduced. Public policy continues to treat the South as a buffer for social cohesion, using redistribution and regulatory forbearance to contain structural exclusion. As a result, Italy’s national growth strategy is fragmented, its cohesion policies perform poorly, and industrial upgrading is confined to regions already integrated into global value chains.

Key contributions

- It develops the concept of a “two-tiered growth regime” to explain the coexistence of divergent regional dynamics within a single country.

- It defines “administrative Keynesianism” as a regime type where the state sustains consumption and employment through public spending, weak enforcement, and social transfers.

- It demonstrates the limits of national-level growth models. Such approaches fail to capture the lived realities of economic divergence in large, regionally heterogeneous countries.

This paper forms the first part of a trilogy on Italy’s growth model and industrial transformation, setting the structural context for subsequent analyses of industrial policy (Part II) and competitive advantages at the firm and regional level (Part III).