Governing Sovereign Risk in the Euro Area

Is sovereign risk in the euro area priced by markets, or designed by policy?

Executive Summary

The ECB’s treatment of sovereign debt now sits at the core of Europe’s financial stability, but its legal mandate leaves the ECB with wide discretion. Since the euro-area crisis, tools such as OMT and PEPP have played a critical role to preserve monetary policy transmission, while “everyday” collateral rules on eligibility, haircuts and credit quality quietly shape sovereign spreads, liquidity and the safe asset status of government bonds. These design choices redistribute risks and borrowing costs across Member States yet are mostly presented as technical details rather than political decisions.

While market discipline has repeatedly failed, it remains embedded via rating-based collateral rules. The pre-2008 compression of spreads and the procyclical downgrades of 2010–12 showed that sovereign yields reflect institutional design and liquidity conditions at least as much as fiscal and economic “fundamentals”. The ECB’s 2005 move to external ratings hard-wired this problem into its collateral framework: downgrades now trigger higher haircuts and the threat of ineligibility, creating cliff effects and a structural periphery premium even in the absence of clear changes in underlying solvency.

Market stabilisation tools were built to fix fragmentation partly created by this framework, but they remain tied to it. SMP, OMT, PSPP, PEPP and TPI were introduced to repair transmission once rating-based eligibility impaired access to safe collateral. Yet most programmes continue to rely on ratings, capital key allocations and opaque conditionality, so that stabilisation depends on the same logic that contributed to previous crises. Rating agencies in turn treat ECB backstops as a key pillar of euro area governments’ creditworthiness, creating a feedback loop in which the ECB and private rating agencies jointly produce the “market signals” the ECB claims to follow.

Sovereign bond markets are shaped by policy choices, but their design is not transparently debated. Choices on conditionality, maturity limits, the exclusion of indexed bonds, use of private ratings and the line between “standard” and “non-standard” tools all carry clear distributive implications. However, the Governing Council has offered little public reasoning on why specific options were chosen, which alternatives were considered, or how trade-offs were weighed. This lack of transparency creates a democratic problem: decisions with fiscal and political consequences are taken largely outside structured parliamentary scrutiny.

Democratic legitimacy requires stronger transparency and parliamentary involvement. The potential of the Monetary Dialogue to clarify the ECB’s choices in its treatment of sovereign debt should be fully tapped into. Debt Management Offices, the Commission, Council bodies and the ECB jointly shape sovereign markets. The European Parliament should demand presence in key fora, notably the ECB’s Bond Market Contact Group and the EFC’s Sub-Committee on EU Sovereign Debt Markets. Guidance by the EP on the secondary mandate can enhance the democratic basis for the ECB’s actions in its approach to sovereign debt.

Policy Recommendations:

We recommend that the European Parliament:

- Employs its accountability toolbox to demand greater transparency of the ECB’s sovereign-debt choices;

- Ensures parliamentary presence in key fora shaping sovereign-debt governance;

- Offers enhanced guidance on the ECB’s secondary mandate.

This document was provided by the Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit at the request of the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON) ahead of the Monetary Dialogue with the ECB President on 3 December 2025.

1. Introduction

The ECB’s treatment of sovereign debt has become central to Europe’s financial stability.[1] Since the euro area sovereign debt crisis, the European Central Bank (ECB) has relied on large-scale government bond purchase programmes to stabilise financial markets and safeguard monetary-policy transmission. The announcement of Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) in 2012 is widely credited with halting the sovereign debt crisis, while the 2020 Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) helped contain a new bond-market panic triggered by the Covid-19 shock. In a world of fragile financial markets, heightened geopolitical tensions and growing climate-related risks, such market stabilisation tools are likely to remain essential. Even as the ECB scales back active asset purchases, design choices in the collateral framework used for “everyday” monetary policy continue to shape the functioning of sovereign bond markets.

Choices in the ECB’s treatment of sovereign debt are not neutral: they entail major economic and distributive consequences. Decisions about which sovereign bonds are eligible, on what terms, and subject to which conditions affect borrowing costs, liquidity and the perceived safety of euro area government debt. Reliance on private credit rating agencies in the collateral framework has been shown to undermine the safe-asset status of some sovereigns and widen spreads (van ’t Klooster 2023; Suttor-Sorel 2023; Claeys & Gonçalves Raposo 2018; Antonini & Mazzocchi 2025). At stake is not only economic efficiency but also how risk is allocated across member states. The ECB has often presented its approach as technical and following its legal mandate. Yet, the legal framework leaves the ECB wide discretion over sovereign debt’s role in monetary policy operations.

The ECB’s approach to sovereign debt raises questions of accountability and legitimacy. The asymmetric design of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) regulates fiscal policy and prohibits direct monetary financing but leaves unresolved how sovereign bonds should feature in the ECB’s toolkit (van ’t Klooster 2023). Within this incomplete legal framework, the ECB has had to develop its own principles for treating government debt. These decisions, though grounded in its mandate, have far-reaching political and distributive implications, creating winners and losers across multiple dimensions. They shape which governments face higher financing costs, how crises propagate through sovereign markets, and how fiscal authorities can respond in an era of repeated shocks. The ECB’s choices often remain opaque. Given the ECB’s independence, these decisions raise democratic questions about whether they should be made exclusively by the central bank. Concerns over the democratic legitimacy of the ECB’s decisions have repeatedly arisen in public debate, as well as in legal proceedings before the European Court of Justice and the German Constitutional Court (de Boer 2023).

This paper analyses the political stakes and design choices in the ECB’s sovereign debt policies and how the European Parliament can respond. Section 2 sets out the key stakes in the ECB’s treatment of sovereign debt in the context of EMU’s asymmetric design. Section 3 traces the evolution of the ECB’s collateral framework, focusing on the pivotal 2005 shift towards a market-based approach. Section 4 examines key design choices in the ECB’s stabilisation instruments, highlighting six areas where eligibility rules and activation criteria have significant political and distributive effects. Section 5 concludes with recommendations on how the European Parliament can improve transparency and enhance its dialogue with the ECB in this area.

2. The puzzle of sovereign debt in ECB monetary policy

The ECB’s legal mandate leaves almost entirely open how the central bank should approach sovereign debt in its monetary policy operations. That means key choices are left to the ECB itself. This section explains the key political stakes in the ECB’s approach to sovereign debt.

2.1. EMU’s asymmetric design and the role of market discipline

The EMU was built on a structural imbalance between monetary and fiscal policy. The Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) was designed around a sharp asymmetry between centralised monetary policy and largely national fiscal policy. Under the Maastricht Treaty, monetary policy became an exclusive EU competence, delegated to an independent central bank with price stability as its primary objective (Borger 2020, p. 114 and further; Hinarejos 2015). Fiscal policy remained with Member States, which continued to issue sovereign debt nationally under shared rules but without a common fiscal authority.

Rules were needed to contain negative spillovers and protect ECB independence. The EMU architects recognised the need to prevent Member States to run excessive deficits, leading to unsustainable debt levels. Policymakers feared that excessive deficits would drive up interest rates for other Member States and private market participants (Grauwe 2014, p. 215 and further), and could fuel inflationary pressures, forcing the central bank to raise interest rates to safeguard price stability by slowing down economic activity (Heipertz and Verdun 2010). Rules were also needed to protect the independent position of the ECB. The fear was that high debt levels and extensive borrowing could put pressure on the ECB to keep interest rates low, or even, monetise sovereign debt. In both cases the ECB’s ability to independently achieve price stability would be affected.

Treaty provisions hardwired some degree of “market discipline” into EMU’s architecture. Article 123 TFEU prohibits monetary financing to block direct deficit funding and shield the ECB from political pressure to buy government debt – which could jeopardise its capacity to uphold price stability as its primary objective. Article 125 TFEU, the “no-bailout clause”, prevents the Union or Member States from assuming the liabilities of others. These provisions aimed to force governments to rely on bond markets, where higher borrowing costs were expected to penalise fiscal indiscipline (Borger 2020; Smits 1997).

Policymakers nevertheless recognised early on that market discipline could misfire. The 1989 Delors Report (the EMU blueprint) warned that market forces might be “too slow and weak or too sudden and disruptive” (Economic Committee for the Study of Economic and Monetary Union 1989, p. 20). That concern is even more salient today: systemic repo fragility (Adrian and Shin 2010), compounded by geopolitical conflict, climate risks, and the rise of digital currencies (cf. Rey 2025) are all sources of financial risks that could increase the likelihood of abrupt and self-reinforcing repricing. The ECB’s recent shift away from strict “market neutrality” towards “market efficiency” principles (Schnabel 2021; Thiemann et al. 2023) implicitly acknowledges that market pricing is dysfunctional. Dysfunctional markets make poor disciplinarians.

The EU fiscal framework was added to address these limits, without resolving the place of sovereign debt in ECB operations. Following Delors’ objection to sole reliance on market discipline, EU governments adopted fiscal rules to constrain Member States’ deficits and debts (Heipertz and Verdun 2010; Segers and van Esch 2007). Article 126 TFEU lays down the ‘excessive deficit procedure’ in case Member States do not comply with the rules and allows for the imposition of sanctions. These Treaty rules were complemented in 1998 with the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), which has since been amended several times (Suttor-Sorel 2021). This framework separated fiscal and monetary responsibilities, yet left unanswered how sovereign bonds should be treated within the ECB’s operational toolkit (van ’t Klooster 2023).

2.2. Sovereign debt at the core of monetary operations

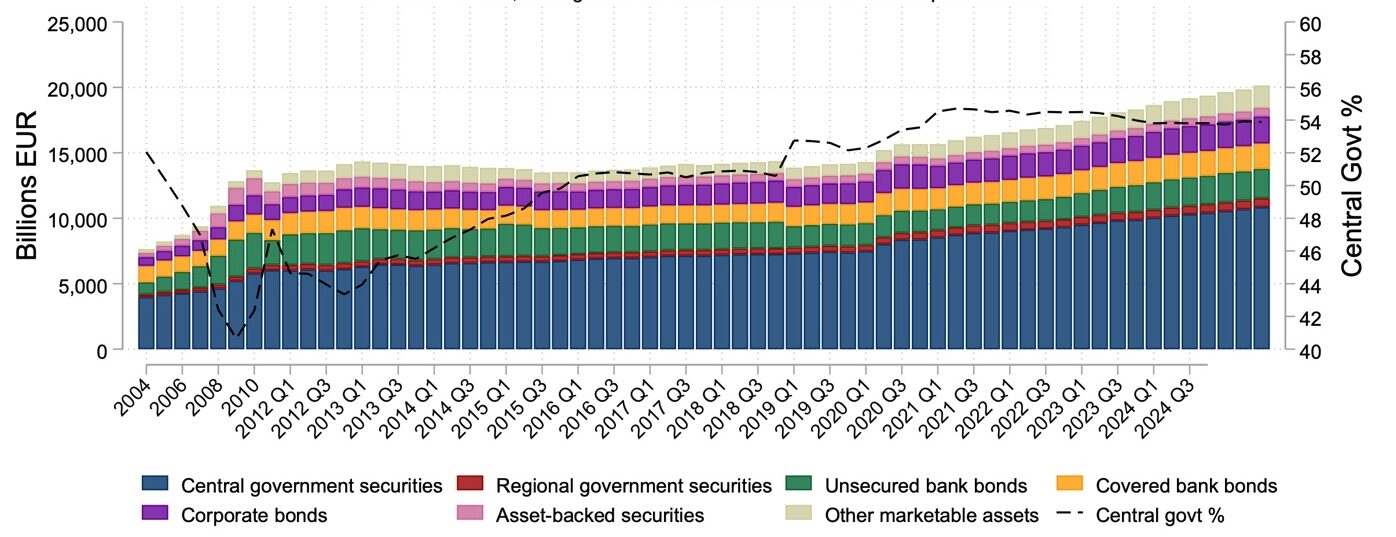

Sovereign debt plays a crucial role as collateral in monetary policy operations. In ‘everyday’ monetary policy, the ECB provides loans against collateral – an asset that a lender can claim in the event of borrower default. Prior to EMU, all Member States’ central banks used government bonds as collateral to conduct monetary policy. Some national central banks did so exclusively, meaning they only accepted sovereign debt instruments as collateral in monetary policy operations. Other major central banks, such as the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, also use government bonds as collateral in monetary policy operations. Today sovereign debt continues to form a large part of the collateral accepted by the ECB (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: ECB Eligible Marketable Assets by Asset Type

Source: ECB. Authors’ visualisation.

Well-functioning sovereign-bond markets are essential for market-based monetary transmission. Sovereign bonds are widely used as collateral in financial market transactions, as they are generally the safest and most liquid assets available. When financial institutions need to post collateral — in repo markets, derivatives transactions, or central bank operations — they require assets that are universally accepted, easily valued, and can be quickly converted to cash.

The ECB’s collateral rules actively shape market valuations rather than simply reflecting existing market conditions. The ECB’s collateral framework determines which bonds banks can use when borrowing from their national central bank. But the framework’s influence extends far beyond these official transactions (Gabor and Ban 2016). Private lenders in Europe’s repo markets — where financial institutions lend to each other using bonds as collateral — follow the ECB’s eligibility rules and risk assessments. A bond treated favourably in the ECB framework commands better terms in private markets, while bonds the ECB penalises with higher haircuts or restricted eligibility face higher costs throughout the system. Beyond their use as collateral, the safety and liquidity of sovereign bonds make them indispensable in several other contexts. Banks hold them as part of their liquidity buffers to meet short-term funding needs. They also form the core of regulatory liquidity requirements, such as the Liquidity Coverage Ratio under Basel III. During stress episodes, investors flee to high-quality sovereign bonds, reinforcing their role as the main safe asset of the euro area. Their deep and active markets also make them the foundation for benchmark yield curves used to price other financial instruments.

Instability in sovereign bond markets poses systemic risks extending well beyond public finances. Due to their wide use as main source of high-quality collateral, disruptions in sovereign bond markets can transmit rapidly through repo markets, derivatives markets and banks’ balance sheets through the whole financial system, hampering ECB’s ability to effectively transmit its monetary policy to the broader economy. The challenge for the ECB is therefore not whether to rely on sovereign debt in operations, but how to govern its use in a way that preserves financial stability and ensures effective monetary transmission.

2.3. Legal vagueness and ECB discretion on collateral policy

EU law authorises the use of sovereign collateral but leaves “adequate collateral” undefined. Article 18 of the Statute of the European System of Central Banks and the European Central Bank (hereinafter: the ESCB Statute) allows the ECB to operate in financial markets and lend against “adequate collateral”, but does not specify what qualifies as adequate. Article 123 TFEU — the prohibition on monetary financing — forbids the direct purchase of Member States’ debt instruments by the ECB or national central banks. It does not, however, rule out their indirect purchase, that is, on secondary markets. The legal framework therefore establishes the ECB’s authority but does not dictate how sovereign debt should be treated within it.

This legal silence leaves the ECB with broad discretion to design collateral policy. Because neither the Treaty nor the Statute defines eligibility criteria or haircuts, the ECB has had to develop its own framework for assessing sovereign collateral. For Member States, these decisions matter considerably: eligibility on favourable terms increases demand for their bonds, improves liquidity conditions and lowers financing costs. Conversely, tighter eligibility rules or higher haircuts can raise yields. This operates through what economists call the “convenience yield.” Investors price benefits beyond expected cash flows (Krishnamurthy and Vissing-Jorgensen 2012; Gorton 2017). As “safe assets,” sovereign bonds provide three valued services: safety, liquidity, and collateral usability. By determining which bonds qualify for central bank operations and at what haircuts, the ECB directly influences the collateral usability component of this yield.

Haircuts are a central mechanism through which the ECB’s collateral framework influences sovereign financing conditions. Suppose a government bond is valued at € 100, applying a haircut of 10% would mean that the central bank’s counterparty can borrow € 90 against this bond as collateral. In this way haircuts protect lenders against counterparty default and market fluctuations (Bindseil & Papadia, 2006, p. 8-9; Gabor and Ban, 2016), but they also shape sovereign yields via three channels. First, lower haircuts reduce banks’ funding costs, as they can obtain more central bank cash against the same collateral, allowing them to accept lower yields on the bonds. Second, bonds with favourable collateral treatment become more liquid — easily convertible to central bank cash — which commands a liquidity premium that lowers yields. Third, generous collateral treatment increases demand for those bonds, as institutions prefer holding assets that serve effectively as collateral across repo markets, derivatives transactions, and central bank operations.

Collateral policy therefore has direct fiscal and monetary implications. By influencing yields, liquidity premia and the perceived safety of sovereign bonds, the ECB’s collateral framework affects the fiscal space available to national governments as well as the effectiveness of monetary-policy transmission. Insofar as these effects support the Union’s economic objectives, they fall within the ECB’s secondary mandate under Article 127 TFEU: “support the general economic policies in the Union with a view to contributing to the achievement of the objectives of the Union as laid down in Article 3 of the Treaty on European Union.” Yet the breadth of the ECB’s discretion also raises questions about how such choices are authorised and scrutinised.

While sovereign bonds are essential for monetary-policy implementation, unconditional acceptance also carries risks. One is that the ECB has reason to safeguard itself against financial risk and avoid potential losses. Another risk is that of moral hazard. Unquestioned acceptance of sovereign bonds as collateral could allow Member States to monetise sovereign debt through the private banking system. That could, in turn, impact fiscal responsibility at the national level and, ultimately, the independent position of the ECB to achieve price stability, as the central bank could be pressured to keep interest rates low in order prevent debt servicing problems at the national level.

2.4. Democratic legitimacy and the ECB’s approach

The ECB’s mandate leaves key choices on sovereign debt treatment to the central bank itself. The central bank could accept sovereign debt as collateral without conditions and leave supervision of national fiscal policies entirely to political institutions under the SGP. Conversely it could also use its collateral policy to enforce fiscal discipline on the Member States, for example, by tying collateral acceptance to compliance with the EU fiscal rules. The ECB could have also chosen to conduct its own credit ratings of sovereign debt, which would have required the ECB to offer its own assessment of national fiscal policies.

This discretion raises questions of democracy legitimacy and accountability. The democratic justification for delegating monetary policy to an independent central bank is commonly understood to rest on two principles (de Boer and van ‘t Klooster 2020; Draghi 2018; Issing 1999; Scheller 2004). First, there must be an act of prospective democratic authorisation: the ECB’s mandate, drafted by political institutions, is intended to define a clear set of powers and the conditions under which they may be exercised. Second, the central bank must be accountable for the use of those powers (Lastra 1992; Magnette 2000; ECB 2025b). For the ECB, this means explaining to the European Parliament how its actions fit within the mandate so that citizens and their representatives can judge their appropriateness.

Historically, the ECB interpreted its mandate as leaving little discretion. It viewed itself as pursuing a single, clearly defined objective – price stability – through a single instrument: the setting of short-term interest rates (de Boer & van ’t Klooster 2020; Grünewald & van ’t Klooster 2023). Price stability was first defined in 1998 as “below 2%” (ECB 1998) and in 2003 as “below, but close to, 2% over the medium term” (ECB 2003). On this interpretation, interest-rate setting was a predominantly technical task involving only limited political judgment. As former ECB Executive Board member Otmar Issing put it, trade-offs between competing objectives “should naturally remain the preserve of democratically elected representatives” (Issing 1999, p. 508-509). Former ECB President Mario Draghi reiterated this view in 2018 (Draghi 2018), stressing that central banks are not meant to decide which goals to pursue, but only how to conduct monetary policy in pursuit of those goals:

Central banks are powerful, independent and unelected. This combination can only be squared if they have a clearly defined mandate for which they are held accountable by the public. It is legislators that define the mandate that establishes the goals of monetary policymaking. And it is legislators that are responsible for holding central banks accountable for the effectiveness of their monetary policy.

Recent crises showed how wide the ECB’s policy discretion actually is. Many commentators have questioned whether the existing democratic justification adequately reflects the ECB’s actual role (e.g: de Boer and van ‘t Klooster 2020; Dawson et al. 2019; Fromage et al. 2019; Grünewald & van ’t Klooster 2023; Högenauer and Mendes 2025). The mandate is far more open-ended than the ECB’s early interpretation suggests. Since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the subsequent sovereign debt crisis, the ECB’s responsibilities and instruments have expanded considerably. The 2021 Monetary Policy Strategy Review formalised these changes and confirmed that the ECB now employs a broader set of tools and considers a wider range of objectives (Grünewald & van ’t Klooster 2023). As part of proportionality assessments, the ECB evaluates whether the positive effects of its instruments on price stability outweigh possible negative side effects.

The resulting democratic challenge can be understood as a democratic authorisation gap (de Boer & Van ‘t Klooster 2020). The ECB now makes choices with significant distributive and political implications for which its mandate provides limited guidance. Whereas the pre-crisis view portrayed monetary policy as involving minimal political judgment, the past decade and a half have shown that the ECB must frequently take decisions not predetermined by its mandate.

The ECB’s treatment of sovereign debt is one of the clearest examples of an authorisation gap. The mandate provides little guidance on how sovereign debt should be integrated into monetary operations, yet the ECB unavoidably has to take a position. Although its choices are not outside its mandate, the mandate does not specify how these decisions should be made. As a result, crucial choices in this area have rested with the ECB since the start of monetary union.

Faced with this discretion, the ECB in practice disavowed its agency. The central bank presented its approach as flowing from its legal mandate, downplaying its own agency (van ‘t Klooster 2023). By framing its approach in this way, the ECB reduced the scope for democratic scrutiny, as it did not clearly explain why it chose one course of action over possible alternatives. As the next section shows, this dynamic is exemplified by the 2005 decision to delegate much of the assessment of sovereign creditworthiness to private credit-rating agencies. Likewise, key policy choices related to the subsequent design of market stabilisation instruments, remained hidden as is discussed in section 4. Further democratic scrutiny and guidance of the ECB’s choices can address this democratic challenge. Such control includes both ex ante dialogue and appropriate guidance from the EP before policy implementation (e.g. on the secondary mandate and its relevance in the context of proportionality assessments) and ex post accountability that supports policy evaluation and learning.

3. The ECB’s 2005 Shift to a Market-Based Collateral Framework

The ECB’s current approach to sovereign collateral and market stabilisation is the product of a decisive shift in 2005. This section retraces that change, explains why it occurred, and analyses its effects on sovereign spreads, crisis dynamics and the broader functioning of the euro-area bond market.

3.1. A pivotal change: from internal assessments to rating-based eligibility

Prior to 2005, collateral eligibility rested on a minimum credit rating defined by the ECB itself. This minimum credit rating system was kept secret and met by all euro area Member States. For that reason, it has been described as effectively having “no teeth” (van ’t Klooster 2023, p. 1109). The ECB faced growing pressure to revise this approach as debates intensified over fiscal discipline and the credibility of EMU’s fiscal rules.

Two developments led to calls on the ECB to use its collateral framework for disciplining Member States. First, the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) had visibly failed to enforce fiscal norms on Germany and France. Both countries breached the SGP in the early 2000s and then resisted the Council’s recommendations, leading to a contentious reform, which, in the eyes of its critics entailed a problematic weakening of the Pact (on these events see Borger 2020, 166–82).[2] Second, financial markets were not discriminating between Member States despite large differences in fundamentals. Following the Maastricht Treaty, sovereign yields converged sharply, with spreads narrowing to negligible levels even though debt levels and other ‘country-specific fundamentals’ varied significantly (Geyer et al. 2004; Hallerberg & Wolff 2008) – see Figure 1 on the following page. Critics argued that, without functioning market discipline, the ECB should introduce stronger differentiation in its collateral framework.

The ECB responded by delegating sovereign credit assessment to private rating agencies. While the ECB was hesitant to use its collateral policy in this way, it chose to adopt a “market-based approach” to sovereign debt. Rather than applying an internal assessment of debt sustainability or rely on compliance with EU-level rules, the ECB effectively delegated authority over this critical monetary policy instrument to private, predominantly U.S.-based rating agencies. Under the new framework, sovereign bonds’ eligibility and haircuts were determined by credit-quality steps mapped from external credit ratings. This represented a major shift in the organisation of sovereign-bond markets in the euro area towards a renewed faith in market discipline.

Table 1: Equivalence between sovereign credit ratings, credit quality steps, and ECB haircuts

Rating scale | Example | Credit quality step | Haircut | |||

Moody’s | S&P | Fitch Ratings | ||||

Aaa, Aa | AAA, AA | AAA, AA | DE, (FR) | 1 | 0.5-6.3% | |

A | A | A | (FR), ES, PL | 2 | 0.5-6.3% | |

Baa | BBB | BBB | IT | 3 | 5.4-14.4% | |

Ba/ B/ Etc. | BB/ B/ Etc. | BB/ B/ Etc. | / | 4/ 5/ 6 | Ineligible | |

Source: Authors; based on: Suttor-Sorel (2023), ECB collateral framework (2022).

3.2. The far-reaching consequences of the 2005 framework

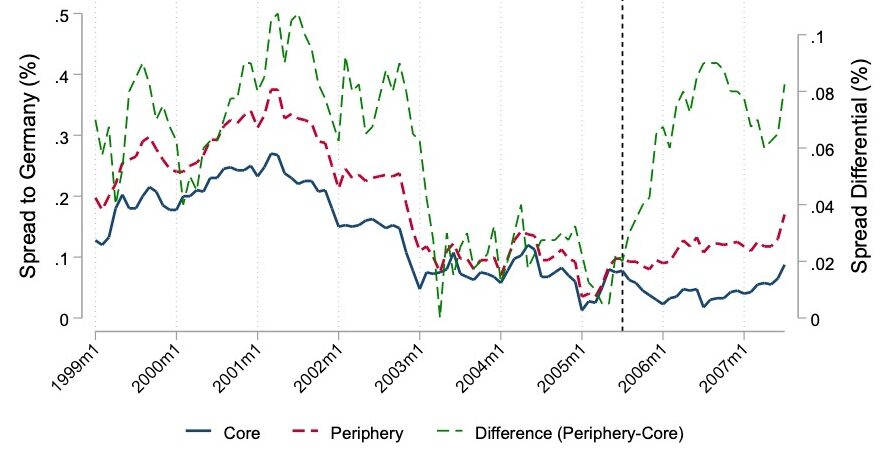

The shift to rating-based eligibility reshaped yield spreads across the euro area. Empirical evidence suggests that the ECB’s new collateral rules, more than economic fundamentals, triggered the reemergence of sovereign spreads in the euro area (Schuster 2023, see also van ‘t Klooster, 2023, Antonini and Mazzocchi, 2025). Post-2005, the ECB’s shift to conditional collateral eligibility signalled that the central bank would allow government defaults, fundamentally changing market perceptions. Markets began pricing a ‘periphery premium’ for countries whose asynchronous business cycles made them more vulnerable to financing constraints under this new conditional framework, even in the absence of weaker fiscal fundamentals. The resulting increase in borrowing costs was substantial: the periphery – relative to the core – experienced spreads rising by up to 20 basis points, effectively doubling yield differentials pre-2005 (Figure 1).

Figure 2: Sovereign Spreads in the Core and Periphery Euro Area

Source: based on Schuster (2023).

Note: Data: Monthly yields on 10-year bonds from Eurostat. Core includes Austria, Belgium, France, and the Netherlands. Periphery includes Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain.

The distributional effects were significant and politically consequential. Higher haircuts and the risk of ineligibility raised funding costs for some Member States. Box 1 illustrates how the increased spreads impact on the capacity of EU Member States to deliver on their defence spending commitments. These outcomes were not the results of a political decision or treaty rule, but of operational choices embedded in the design of collateral policy.

The ECB’s market-based treatment of sovereign debt played a central role in the 2010–2012 euro area crisis (e.g. De Grauwe, 2011; Gabor and Ban, 2016; Orphanides, 2014). By relying on private credit ratings and relinquishing the discretion to diverge from them, the ECB exposed itself to systemic risk. Downgrades of individual Member States led the ECB to impose higher haircuts on their debt when pledged as collateral. This factor made it less attractive for market participants to hold these states’ sovereign debt. In addition, credit downgrades of these Member States’ debt raised the risk that their bonds would become ineligible as collateral at the ECB. Market participants anticipated and hedged potential downgrades of other states, creating an endogenous crisis driven by the interaction of collateral rules and market behaviour. Rather than passively reflecting market fundamentals, the ECB’s collateral framework created differentiation between Member States, with seemingly technical rules translating rating agency assessments into market hierarchies.

3.3. Market stabilisation tools as a response to collateral policy-driven fragmentation

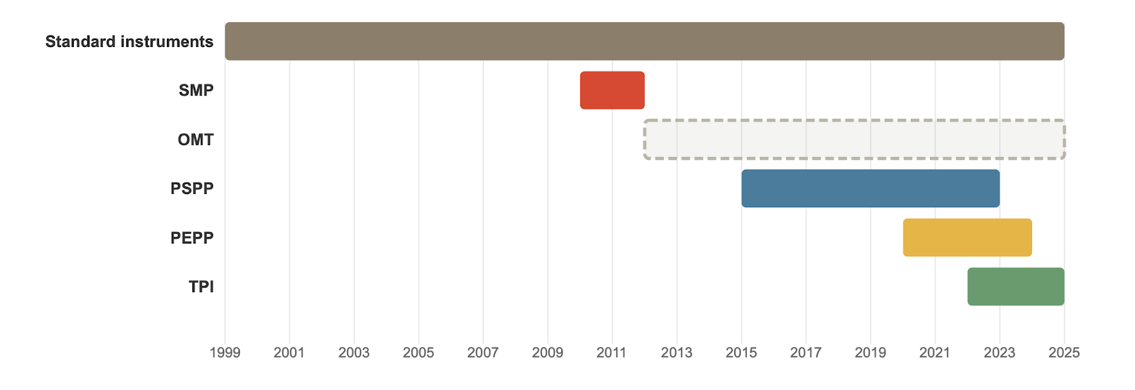

The ECB developed a new stabilisation toolkit to counteract the problems partly created by its own collateral framework. Once sovereign collateral eligibility depended on private ratings, downgrades fed directly into higher haircuts, reduced liquidity and rising spreads. By the end of the 2000s, this collateral-induced differentiation contributed to broader impairments in monetary policy transmission forcing the ECB to intervene. The result was the creation, over the next decade, of a series of market-stabilisation instruments: large-scale asset purchases, such as the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) and the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP); liquidity backstops; and explicit anti-fragmentation tools, including Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) and the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI).

These tools were designed to repair fragmentation, but their effectiveness remained tied to the same rating-based logic that had contributed to the problem. While SMP, OMT and TPI allowed targeted intervention, the APP and PEPP broadly adhered to the capital key and to credit-quality thresholds derived from private ratings. Eligibility remained sensitive to rating movements. During the pandemic, the ECB ultimately suspended rating thresholds by “grandfathering” collateral eligibility — an implicit acknowledgement that the framework’s procyclicality had become destabilising. The stabilisation toolkit thus evolved as a corrective overlay to a collateral regime that itself shaped market stress.

At the same time, rating agencies incorporate ECB backstops into their sovereign ratings. Rating agencies treat euro-area membership, ECB liquidity support, crisis-response tools and the overall credibility of the monetary regime as important components of a sovereign’s external and institutional strength, among other factors – see box 2 for more on sovereign credit ratings methodology. The ECB thus depends on ratings that themselves embed the ECB’s market stabilising power.

This circularity means market signals are not “exogenous” inputs but jointly produced by the ECB and rating agencies. When the ECB expands its market stabilisation toolkit – such as OMT, PEPP or TPI – rating agencies are incentivised to revise upward their assessments of sovereign creditworthiness. These stronger ratings then feed back into the ECB’s collateral framework, reducing haircuts, widening eligibility and lowering borrowing costs. Conversely, if rating agencies threaten downgrades, the ECB must either tighten collateral rules – amplifying spreads – or suspend rating thresholds, as it did under PEPP in 2020. Though mediated through market mechanisms, the result is a system in which the ECB and rating agencies mutually reinforce each other’s judgements, even as their roles are formally distinct.

Recognising this loop is essential for evaluating the ECB’s sovereign-debt policies. If ratings embed the ECB’s own market stabilising capacity, treating them as neutral, external benchmarks becomes analytically misleading. It obscures the ECB’s role in shaping spreads, masks the political nature of collateral rules and underplays how monetary governance structures sovereign-risk differentiation across the euro area. Understanding this feedback loop is therefore a prerequisite for assessing the ECB’s policies and for defining credible transparency and accountability reforms.

The contrast with the pre-2005 period highlights the political contingency of euro-area spreads. When collateral eligibility was uniform, spreads were minimal, supported by convergence dynamics and market assumptions about implicit guarantees. Once eligibility was tied to private ratings, differentiation widened and became crisis-sensitive. Euro area sovereign spreads have evolved in ways that question the notion that the ECB merely mitigates market disruption. The ECB’s policies in themselves significantly impact the operation of bond markets.

4. Policy design choices in market stabilisation policies

Sovereign bond markets are not neutral arenas, but political constructions shaped by law, regulation and central bank policies. The structure of euro area sovereign markets — from liquidity to safe asset status and the pricing of risk — reflects choices embedded in EMU’s legal framework, banking regulation, and, crucially, the ECB’s collateral rules (Pistor, 2013). Market stabilisation tools therefore do not respond to an external, pre-existing “market”; they operate within a system the ECB itself helps create. Yet many of the design choices behind these tools — which determine eligibility, haircuts and activation conditions — have been presented as technical necessities rather than decisions with political and distributive consequences.

This political nature of market design is insufficiently recognised in published ECB materials. The Governing Council has rarely disclosed how alternative design options were weighed, why certain eligibility criteria were selected, or which trade-offs were considered. While market participants interacting with NCBs can infer operational details, parliaments and the broader public cannot observe how these choices shape spreads, liquidity and sovereign financing conditions.

The following section examines six critical design choices in non-standard market stabilisation tools, each raising distinct questions about eligibility criteria and activation mechanisms: (1) whether an instrument is treated as part of the standard toolkit or reserved for crises; (2) whether purchases follow “market neutrality” (capital key) or a more selective approach; (3) whether sovereign eligibility is tied to compliance with rules such as the conditions attached to an ESM Credit Facility (e.g., ECCL), to the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) or to RRF plans; (4) which maturities qualify; (5) whether indexed securities are included or excluded; and (6) how credit-quality thresholds based on ratings are applied. Table 2 summarises how these choices differ across SMP, OMT, PSPP, PEPP and TPI.

Since these choices are insufficiently documented, our analysis reconstructs them from dispersed sources. Eurosystem communication rarely presents these design parameters as political or distributive choices among alternatives. In the absence of transparent, systematic justifications, our assessment relies on a combination of empirical and theoretical research, close reading of legal acts and public documents, and the “subtext” of speeches, blog posts, interviews and ECB or NCB communications. More transparency about expectations, causal assumptions and trade-offs is needed given the magnitude of the distributive effects involved. These design decisions should be recognised and debated as matters of political choice, not merely of technical expertise. Meanwhile market participants gain operational understanding of policy choices that is not matched by public documentation. As ECB counterparties, they know operational terms, blackout periods, and transaction details; as secondary market participants, they possess real-time information on market direction and flows. Even ex post, comprehensive reporting of these operational choices (including what is excluded and why) remains inadequate for democratic scrutiny. This creates a significant information asymmetry between market insiders and the public.

Figure 3: The ECB’s market stabilisation tools

Source: Authors’ compilation.

Table 2: Overview of design choices in the ECB’s market stabilisation tools

|

|

Standard vs. Non-standard |

Market neutrality |

Conditionality |

Maturity of assets purchased |

Exclusion of inflation-indexed bonds |

Credit quality requirements |

Mode of publication |

SMP (2010) | Crisis instrument | No (selective) | No (informal) | Short/medium term | Yes | n.a. | Legal act |

OMT (2012) | Crisis instrument | No (selective) | Yes (EFSF/ESM) | Short term (1–3 years) | not specified | n.a. | Press release |

PSPP (2015) | Standard since 2021 | Yes (capital key) | No | 1 year – 30 years 364 days | No | CQS 3 or higher | Legal act (ECB/2015/10) |

PEPP (2020) | Standard since 2021 | Yes (capital key), but flexible | No | 70 days – 3 years 364 days | No | CQS 3 or higher, except for Greece | Legal act (ECB/2020/17) |

TPI (2022) | Crisis instrument | No (selective) | Yes (SGP, RRF, NGEU) | 1–10 years | Not specified | n.a. | Press release |

Consequences | Degree of uncertainty about conditions for activation; signal in case of activation | Proportional (“neutral”)/disproportionate effects on price discovery and price level in select market segments/jurisdictions; economic inefficiency of central bank action | Uncertainty; market turmoil; risk premia induced by insecurity on central bank action | Effects on the yield curve; effects in real markets related to the relevant assets (e.g. housing markets for long-term interest curve) | Effects on sovereign budgets/debt management offices | Dependence upon a closed group of private actors (mostly US except for one GER Credit Rating Agency); uncertainty about central bank action; risk premia | Legal uncertainty about motives, activation, further implementation, eligibility etc. |

Source: Authors’ compilation

4.1. Policy choice 1: Categorization as “standard” vs. “crisis” instrument against “unjustified” market behaviour

The “non-standard” label hides a gradual normalisation of crisis tools without clear criteria for their use. Since 2008, the ECB has introduced a series of new monetary policy instruments, originally termed “non-standard measures.” Over time, several have been integrated into the central bank’s conventional toolbox (cf. ECB 2021, para. 8). Yet there is no publicly articulated framework clarifying when a measure is considered “standard” or reserved for exceptional circumstances, or when a situation qualifies as a “crisis” that justifies activating special tools.

Key concepts such as “unjustified” stress or “departures from fundamentals” remain vague and contested. The ECB often presents asset purchases and backstops as temporary responses to “unwarranted” fragmentation, “unjustified” market reaction or deviations from “fundamentals” (ECB 2022). But what counts as “unjustified” movements in yields or “fundamentals” is not objectively given. It depends on normative and institutional choices about how sovereign risk should be priced – choices in which the ECB itself is a central actor.

Through its operational framework, the ECB actively shapes the very markets it claims to be correcting. Collateral rules, eligibility criteria, and signalling of acceptable risk premia, continuously shape the structure and functioning of sovereign bond markets. In this sense, markets are not neutral arenas that the ECB merely corrects when they malfunction; they are politically and legally engineered spaces, co-produced by monetary governance. While interventions may well be warranted in principle, their justification remains broad and qualitative. There is no clear litmus test for when markets are “stressed,” “malfunctioning,” or “fragmented,” leaving substantial discretion in ECB judgment. The distinction between ‘standard’ and ‘non-standard’ tools is similarly blurred: the monetary policy stance is determined not by interest rates alone but by the composition of the central bank’s balance sheet.

In this environment, the activation of “crisis” tools is a matter of discretion, not objective thresholds. There is no objective definition for the question what policy tools are “standard” and which are “exceptional”, and what market behaviour is “justified” or “irrational” – at least, such a definition has never been made public. Instead, the activation of crisis instruments – for example the potential use of the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) – remains entirely at the discretion of the Governing Council. It remains unclear what circumstances the Governing Council would perceive as “unwarranted, disorderly market dynamics that pose a serious threat to the transmission of monetary policy across the euro area“, what criteria the Governing Council applies in its “comprehensive assessment of market and transmission indicators”, when it would take the view that a “durable improvement in transmission” has taken place, or what “country fundamentals” would be taken into account by the ECB (cf. ECB 2022). Its members, however, maintain that “The criteria are publicly accessible and clearly defined – anyone can read them for themselves”, yet feeling the need to add: “I won’t comment on any further details.” (Luis de Guindos 2025). In other words, the criteria deliberately lack “further details”, maintaining ambiguity that creates differential effects: whilst this flexibility may enable effective ECB intervention, it also transfers Eurosystem uncertainty into risk premia borne unevenly by public issuers across member states.

Similar considerations apply to the issue of “phasing out” or “exiting” from crisis instruments. Framing the issue as one of “phasing out” or “exiting” from crisis instruments obscures a more fundamental point: market stabilisation is now a permanent feature of ECB operations, not a temporary aberration. This encompasses not only sovereign bond holdings but also collateral frameworks, liquidity provision, refinancing operations, and the full array of tools through which the ECB continuously shapes markets. The relevant question is then not whether to exit market stabilisation but rather when and how to scale down specific interventions, and crucially, who bears the costs of tightening. Reductions in ECB support carry distributive consequences just as expansions do, whether through unwinding bond holdings, tightening collateral eligibility, or closing liquidity facilities. A 2022 Bundesbank report, for instance, estimated that “reductions in Eurosystem holdings are likely to have a positive impact on market conditions for Bunds” due to the alleviation of scarcity effects created by Bundesbank purchases (Deutsche Bundesbank 2022). Similar distributional dynamics apply across stabilisation tools.

4.2. Policy choice 2: “Market neutrality” and capital-key allocation

The ECB’s “market neutrality” principle masks distributional choices. The ECB has long maintained that monetary policy should be “neutral in the sense that it did not change the relative prices of financial assets” (Bindseil and Papadia 2006; van’t Klooster and Fontan 2020). The ECB’s asset purchases likewise claim to follow the principle of “market neutrality” (ECB 2025a). Initially, the operationalisation of market neutrality saw the ECB purchasing securities in proportion to their relative market capitalisation (Cœuré 2015). This restricted its market stabilisation. Instead of market capitalisation, sovereign bond purchases became guided by the Eurosystem capital key subscriptions: In the Public Sector (PSPP) and the Pandemic Emergency Purchase (PEPP) Programmes, purchases of public sector securities by NCBs were to be proportional to NCBs’ capital key subscriptions under Articles 28(2) and 29(1) of the ESCB Statute (ECB Decisions (EU) 2015/774, Art. 6(2)(2) and (EU) 2020/440, Art. 6(1)). Conversely, the Securities Market Programme (SMP), the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) programme and the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) allowed “selective” purchases of select Member States.

Capital key purchases are presented as neutral, but they have heterogeneous effects across Member States.[3] The “market neutral” design prioritizes the appearance of neutrality toward national budgets and fiscal policies, allowing the ECB to stabilize distressed markets without appearing to “pick winners”—even if this means using more “ammunition” in the Euro area than would be necessary under a targeted (i.e., selective) approach.

By claiming to merely “reflect” markets, the ECB obscures its role as a constitutive actor in market formation. This claim is, however, economically untenable. Market microstructure theory demonstrates that price formation, liquidity provision, and information aggregation are interdependent processes, not separable policy targets (Morris and Shin 2002). When a central bank commits to interventions, market participants incorporate these rules into pricing. Markets price the promise of support or the spectre of its refusal, inducing an “ambiguity premium”. The capital key allocation rule signals which sovereigns receive support, how much and under what conditions, fundamentally altering how private actors assess sovereign risk. Price discovery in the presence of such rules cannot be separated from those conditions — it reflects expectations about intervention.

This approach creates economic inefficiencies. The impact of public securities purchases on sovereign yields is inherently heterogeneous across Member States. Countries experiencing market stress, with high spreads and lower liquidity, see the largest marginal effect from the same proportional purchase. While in stressed markets, small purchases or even just the credible announcement of support can dramatically lower yields, the effect in well-functioning markets is limited. Non-standard monetary policy measures produced stronger marginal effects on bond yields in peripheral countries than in core economies (e.g. Fendel and Neugebauer 2020; Hondroyiannis and Papaoikonomou 2022). Examining the four largest euro area members – Germany, France, Italy, and Spain – Corradin, Grimm, and Schwaab (2021) similarly find that unconventional monetary policy announcements had significantly more beneficial effects on the 5-year bond yields of Italy (13.10% of the capital key) and Spain (9.67%) than on those of Germany (21.77%) and France (16.36%).

Capital key constraints misdirect support away from stressed markets. The capital key constraint means that the biggest part of resources is allocated to comparatively well-functioning markets, while stressed markets receive support constrained by capital key shares that may not reflect their stabilization needs, but the respective Member State’s population and GDP (cf. Article 29(1) and 29(3) of the ESCB Statute). As the euro area’s benchmark country, German bunds benefit from a dual structural advantage during market stress: bunds receive ECB support through capital-key purchases while simultaneously attracting flight-to-quality flows from investors fleeing peripheral bonds.

4.3. Policy choice 3: Conditionality to compliance with SGP, NGEU, RRF or ESM

Conditionality now links market stabilisation to EU economic governance, but on opaque terms. Across the different market stabilisation programmes, the ECB has regulated sovereign debt eligibility through direct (e.g. OMT and TPI) and indirect (e.g. SMP) conditionality, which can be understood to address the problem of moral hazard. Conditionality has become a channel through which EU economic governance interacts with monetary policy, guaranteeing that the ECB’s monetary policy does not “work against the effectiveness of the economic policies followed by Member States” (cf. CJEU 2015, para. 60 on EFSF/ESM conditionality).

TPI eligibility depends on a broad and discretionary set of criteria. Purchases under the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) are conditional to a cumulative list of criteria for the Governing Council to assess whether the relevant jurisdictions “pursue sound and sustainable fiscal and macroeconomic policies” (ECB 2022). This assessment draws on a cumulative list of factors: (i) whether the country is subject to an excessive deficit procedure or has failed to follow Council recommendations under Article 126(7) TFEU; (ii) whether it faces an excessive imbalance procedure or has disregarded corrective action under Article 121(4) TFEU; (iii) fiscal sustainability analyses from the Commission, ESM, IMF and ECB; and (iv) compliance with Recovery and Resilience Plan commitments and European Semester recommendations. The Governing Council retained discretion in weighing these factors and adjusting its evaluation framework based on specific circumstances, retaining its ambiguity as to possible activation of the TPI if deemed necessary and justified.

Withholding TPI support acts as a de facto financial sanction. If a Member State is deemed non-compliant, the absence of TPI support manifests as higher borrowing costs paid to private market participants – an implicit penalty outside the formal European fiscal framework.

Conditionality is presented as a technical monetary policy necessity rather than as a choice with profound implications. Under the SMP, conditionality was informal and designed by the ECB itself (Beukers 2013). In August 2011 the central bank sent confidential letters to the Italian and Spanish governments demanding detailed economic reforms and measures to ensure fiscal discipline (Draghi and Trichet 2011; Trichet and Fernández Ordóñez 2011). This practice exposed the ECB to criticism that it was imposing its will on Member States’ fiscal and economic policy choices. The OMT and TPI framework marked a democratic improvement as they tie ECB interventions to politically agreed conditionality, rather than the ECB own choices. Still, the TPI framework offers limited transparency about how conditions are set and assessed. The framework’s design appears as a technical or legal necessity, obscuring fundamental choices about the relationship between market stabilisation and economic policy.

The ECB risks exposing itself to accusations of technocratic overreach and political interference in national economic policy. This creates reputational risks that threaten the very independence the ECB seeks to protect. Greater democratic accountability regarding conditionality criteria would paradoxically strengthen rather than undermine the ECB’s position: transparent frameworks that acknowledge the economic policy dimensions of crisis interventions are more defensible than technical claims that deny their political significance.

4.4. Policy choice 4: Eligibility criteria regarding maturity

Maturity choices in stabilisation tools reflect discretionary compromises, not clear monetary policy logic. Member States issue bonds from short-term bills to 30-year securities, and the ECB’s programmes have applied very different maturity criteria. These choices were never prescribed by the mandate and instead emerged from a mix of economic, legal and political considerations exercised through ECB discretion.

OMT’s restriction to 1–3-year maturities prioritised legal defensibility over economic coherence. The ECB’s initial decision to limit Outright Monetary Transactions (OMTs) to the “shorter part of the yield curve” with maturities of one to three years was intended to preserve what it termed a “close link to traditional monetary policy” (ECB 2012; 2012a). This design choice strengthened the programme’s legal defensibility by aligning it with short-term interest rate operations and distancing it from monetary financing, while limiting the scope of eligible securities to address “severe cases of malfunctioning in the price formation process”.

Economically, this narrow focus was debatable and risked leaving broader fragmentation unresolved. Monetary policy transmission, the stated aim of OMT, operates along the entire yield curve. The euro area crisis involved not only short-term funding pressures, but also deep-seated confidence failures across the maturity spectrum (e.g. Arghyrou & Kontonikas 2012). Restricting intervention to the short end risked treating only part of the underlying fragmentation while focusing on segments already benefiting from liquidity support via repo markets, central-bank refinancing operations and DMO lending facilities. These mechanisms mitigated, but did not eliminate, stress and were less present at longer maturities.

Subsequent programmes implicitly acknowledged this by extending purchases along the yield curve. Later programmes, such as the PSPP and the PEPP, justified long-term purchases as necessary to “further enhance” the transmission of monetary policy (ECB Decisions (EU) 2015/774, recital 2; (EU) 2020/440, recital 2). These programmes expanded maturity coverage to 30 years and 364 days, while progressively lowering minimum maturities (two years, then one year for PSPP, and 70 days for PEPP).

OMT’s restriction to short maturities reflected legal and political accommodation more than economic rationale. The maturity restriction in OMT to shorter-term securities appears driven not purely by economic reasoning (transmission concerns, balance-sheet risks) but also by legal and political accommodation, reflecting the ECB’s effort to safeguard its institutional legitimacy through self-imposed limits on purchase volumes. The grounds for such accommodation could have been subject to closer public scrutiny and debate, enabling MEPs to perceive, to consider and to ponder the importance and cost of partial ECB (in)action against those of potential public scrutiny.

4.5. Policy choice 5: Exclusion of indexed securities

The ECB’s choice to exclude indexed bonds from SMP purchases was discretionary and had major market effects. In the SMP, the ECB decided to purchase only nominal bonds with fixed coupons and to exclude inflation-indexed and variable-rate securities. This decision was not made public and was taken without consultation with stakeholders. Though clear to market participants and debt managers alike, it remained a matter of ECB discretion.

The exclusion materially widened spreads on certain Italian securities during the crisis. In 2011, spreads on Italian inflation-indexed securities, variable-rate bonds and longer-maturity instruments (15- and 30-year) widened substantially relative to other Italian bonds, precisely because these instruments did not qualify for ECB support as backstop purchases (Ministero dell’Economia e delle Finanze 2012).

The choice reflected long-standing central-bank scepticism of indexation. This scepticism drew on the “oil slick thesis,” which held that inflation-linked bonds could fuel or spread inflation expectations (CGFS 2011). Central bankers argued that if price stability was credible, there should be no need for inflation protection. Debt managers, by contrast, emphasised low borrowing costs and strong demand from pension and insurance investors.

The public had no visibility into this selective support despite its fiscal consequences. Only insiders knew SMP purchases excluded indexed bonds. Parliaments and the public, though bearing the fiscal consequences, had no way to observe this design choice ex ante. External observers could only infer it ex post by analysing market divergences and deducing likely ECB behaviour. This information asymmetry illustrates how operational discretion can significantly affect Member States’ budgets without commensurate democratic scrutiny.

4.6. Policy choice 6: Credit Quality requirements

The ECB uniquely relies on external ratings to assess sovereign collateral. Unlike the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England or the Bank of Japan, the ECB does not automatically treat all euro area sovereign bonds as eligible collateral. Since 2005, the ECB has differentiated sovereign debt through credit-quality thresholds mapped from private rating agencies, subjecting lower-rated Member States to higher haircuts and the risk of ineligibility (Lengwiler and Orphanides 2024). The ECB approach reflects a belief in “market discipline” and adherence to the principle of “market neutrality” , assuming that markets know best when a State’s fiscal and economic policy should be disciplined by higher interest rates/yields. In its PSPP judgment, the German Constitutional Court elevated credit quality requirements toward being one of the reasons why it considered that the PSPP did not – yet – qualify as a circumvention of the prohibition of monetary financing under Art. 123(1) TFEU (BVerfG, PSPP, para. 216). This raises questions about the constitutional importance of credit rating agencies, although it should be added that the ECB, as a matter of EU law, is under the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice.

Rating thresholds generate cliff effects and reinforce market stress. Under PSPP, only bonds rated at least Credit Quality Step 3 (roughly BBB-) were eligible (Decision (EU) 2020/440, Art. 3(2)), while PEPP temporarily allowed Greek bonds rated CQS 4 on the condition that they had been CQS 3 on 7 April 2020. When the ECB “grandfathered” collateral eligibility on 22 April 2020, it effectively suspended reliance on ratings because maintaining it would have triggered destabilising downgrades. These thresholds create well-documented cliff effects: when eligibility depends on rating notches, the mere threat of a downgrade widens spreads, raises banks’ funding costs, and can induce self-fulfilling liquidity spirals (Lengwiler and Orphanides 2024). Crucially, market perceptions of sovereign risk are endogenous to central bank support, meaning the ECB’s own framework shapes the very risks it claims to be protecting against.

Differentiated collateral treatment acts as an implicit sanction outside formal EU procedures. Unlike formal fiscal penalties under the SGP, which flow to the EU budget and require political decisions, this implicit penalty takes the form of higher interest payments to private market participants and is triggered automatically rather than through democratically authorised procedures. Because activation depends on rating movements rather than political deliberation, it bypasses Council oversight and generates procyclical tightening precisely when monetary policy aims to stabilise markets. The result is a system in which a technical feature of the collateral framework carries fiscal and distributive consequences normally associated with political choices.

4.7. Policy choices: Summary

This section has shown that euro-area sovereign markets are shaped as much by policy design as by underlying fundamentals. The ECB’s stabilisation tools operate within – and reinforce – a market structure the central bank itself helps produce. Recognising this political dimension of ECB action is essential for identifying where transparency, scrutiny and parliamentary engagement are needed. Section 5 sets out ways to strengthen those mechanisms.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

The ECB’s treatment of sovereign debt carries significant political and distributive implications. The ECB’s 2005 turn to a market-based approach in its collateral framework undermined the safe asset status of sovereign debt and widened spreads. Together with other factors, the ECB’s new approach contributed to financial instability and the bond market panic during the subsequent 2009-2012 euro area sovereign debt crisis. The introduction of market stabilisation instruments to address this instability is partly a response to the ECB’s own policies.

The ECB’s market stabilisation instruments rest on contestable policy choices. As identified in this paper, the ECB’s choices on the distribution of sovereign debt purchases, eligibility criteria and conditionality, all affect Member States’ borrowing costs and can be questioned for their economic efficiency and distributive consequences.

Democratic legitimacy of the ECB’s approach can be strengthened through enhanced political guidance and accountability. Given that the ECB is an independent institution, its mandate has a key role in the central bank’s democratic legitimacy. The mandate is drafted by political institutions and intended to lay down a well-defined set of powers. While the ECB’s choices regarding sovereign debt are not outside its mandate, this mandate offers only limited guidance on how the ECB should decide. Further political guidance on how the ECB should weigh trade-offs would provide enhanced democratic authorisation for this key area at the intersection of monetary and economic policies.

Democratic accountability is hampered by a lack of transparency. Transparency is a prerequisite for holding the ECB accountable (Bovens 2007, Braun 2017, Curtin 2017, Zilioli 2016). An assessment of the ECB’s choices is only possible when sufficient information is available about them, their consequences and possible alternatives. Yet the ECB’s choices in its approach to sovereign debt remain opaque. The ECB tends to present its choices as technical and flowing from its mandate. This obscures the central bank’s agency. It also limits the possibility of open debate on the ECB’s policy choices and alternatives. In some cases, it is not even clear what the ECB’s choices entail in practice. Examples include the criteria for introducing non-standard monetary policy measures or how the ECB’s Governing Council applies conditionality requirements for activating asset purchases.

Democratic control should be exercised through both ex ante guidance and ex post accountability. Before policy implementation, democratic institutions can provide political guidance, including debate and engagement on policy changes, as well as well-defined indications on how the ECB’s secondary mandate should be interpreted. This guidance is particularly relevant in the period between an announcement of policy change and its implementation (see e.g. ECB, 2025d). Such guidance is not in conflict with the ECB’s independence, because the ECB remains in charge of determining how guidance on secondary objectives is to be reconciled with its price stability objective. After policy implementation, democratic control takes the form of ex post accountability, involving scrutiny of policy design choices in a way that lays bare the distributional and political outcomes. Ex post accountability should facilitate learning and support improved policy design over time. Both ex ante political guidance and ex post accountability require transparency and participation in relevant fora.

Against this backdrop, we offer three main recommendations:

- Employ the European Parliament’s accountability toolbox to demand greater transparency. More transparency from the ECB is required for the European Parliament to understand the consequences of the ECB’s sovereign debt approach and to assess possible alternatives. This requires more openness by the ECB on how decisions in its approach to sovereign debt are made, further details on what key choices entail, and explanations of why alternatives were rejected – including in the context of the proportionality assessment.

Members of the European Parliament have previously questioned the ECB on its collateral framework, for example regarding reliance on external rating agencies and the process related to collateral policy refinement (ECB, 2015, ECB, 2025c). However, the ECB’s answers remain vague, emphasising the ECB’s broad discretion. The EP should request further details regarding specific policy design choices and the decision-making processes. The ECB’s explanations should enable a critical assessment of the relevant policy choices in a clear and understandable manner. If necessary, such answers may be provided confidentially. - Ensure European Parliament presence in and engagement with key fora shaping sovereign debt governance. Governance of sovereign markets occurs in venues that bring together private and public actors: notably the ECB’s Bond Market Contact Group and the Economic and Financial Committee’s Sub-Committee on EU Sovereign Debt Markets. These venues represent distinct institutional perspectives – one hosted by the ECB, the other by national debt managers – yet the European Parliament is absent from both. Parliamentary engagement with public and private actors in sovereign debt markets is essential for two reasons.

First, it would enable ex ante dialogue and guidance. Gaining insights into ongoing discussions about bond market functioning, emerging constraints, and evolving practices would allow Parliament to anticipate where stabilisation pressures may emerge and what operational choices the ECB faces. This knowledge is essential for informed dialogue, in particular where transparency around policy design remains low.

Second, participation would enable ex post accountability: direct knowledge of deliberations in both venues would equip Parliament to ask targeted questions about the choices made and not made in market stabilisation. In addition, the EP should consider further expanding the Monetary Dialogue and developing further dialogue with private actors (e.g. primary dealers) to enable accountability of key actors shaping sovereign debt markets in the EU. - European Parliament’s guidance should focus on the ECB’s secondary mandate. As we have shown in this paper, the ECB’s collateral framework and market stabilisation instruments have obvious ramifications for broader economic policy in the Union. Without prejudice to maintaining price stability, the secondary mandate requires the ECB to “support the general economic policies in the Union with a view to contributing to the achievement of the objectives of the Union as laid down in Article 3 of the Treaty on European Union” (Article 127 TFEU). The supportive nature of the secondary mandate means that the ECB needs to defer to the decisions on economic policies and prioritisation of secondary objectives by EU political institutions (de Boer, Grünewald and van ‘t Klooster 2024; Ioannidis, Hlásková Murphy, and Zilioli 2021; van ’t Klooster and de Boer 2023). Where the ECB has different courses of action to achieve its price stability objective, the central bank is required to choose the course of action that best supports EU political institutions’ decisions on economic policies and secondary objectives.

Guidance by the EP would facilitate the ECB’s implementation of its secondary mandate, which is binding but highly indeterminate by itself. In 2023 the EP suggested to “provide input to the ECB on the secondary objectives” (EP 2023) in its yearly resolution on the ECB, a possibility welcomed by the ECB itself (ECB 2023). Going forward, the EP could expand on its use of this option to enhance the democratic basis for the ECB’s actions choices in its approach to sovereign debt.

Such guidance does not compromise the ECB’s independence, since it leaves it to the ECB to determine in what manner guidance on secondary objectives should be reconciled with its primary objective of price stability (de Boer, Grünewald and van ‘t Klooster; van ‘t Klooster & de Boer 2023; Grünewald & van ‘t Klooster 2023). Moreover, such guidance is particularly relevant in the context of proportionality assessments involving the weighing of different policy options for their potential impacts and trade-offs.

Lastly, another legal avenue could help clarify the ECB’s treatment of sovereign debt: targeted reform of the ESCB Statute governing the ECB’s permissible operations. Under Article 129 TFEU, the Council and the European Parliament may amend selected parts of the Statute through the ordinary legislative procedure. A further option is provided by the Council’s power to clarify the monetary financing prohibition under Article 125 (2) TFEU. This legal basis, however, offers the EP a merely consultative role.

References

- Adrian, T., & Shin, H. S. (2010). Liquidity and leverage. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 19(3): 418.

- Antonini L. and Mazzocchi R. (2025). The silent hand of central banking: collateral framework, EGOV Indepth Analysis, European Parliament.

- Arghyrou, M. G., & Kontonikas, A. (2012). The EMU sovereign-debt crisis: Fundamentals, expectations and contagion. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 22(4): 658.

- Beukers, T. (2013). The New ECB and its Relationship with the Eurozone Member States: Between Central Bank Independence and Central Bank Intervention. Common Market Law Review 50: 1579.

- Bindseil, U. and Papadia, F. (2006). Credit Risk Mitigation in Central Bank Operations and Its Effect on Financial Markets: The Case of the Eurosystem, ECB Occasional Paper Series.

- de Boer, N. and van ’t Klooster, J. (2020). The ECB, the Courts and the Issue of Democratic Legitimacy after Weiss. Common Market Law Review, 57(6): 1689.

- de Boer, N. (2023). Judging European Democracy: The Role and Legitimacy of National Constitutional Courts in the EU. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press.

- de Boer, N., Grünewald, S. and van ‘t Klooster, J. (2024). The law and politics of independent policy coordination: fiscal and sustainability considerations in the European Central Bank’s monetary policy. European Banking Institute Working Paper Series no. 172, https://ssrn.com/abstract=4827387.

- Borger, V. (2020). The Currency of Solidarity: Constitutional Transformation during the Euro Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bovens, M. (2007). Analysing and Assessing Accountability: A Conceptual Framework. European Law Journal 13(4): 447.

- Braun, B.(2017). Two sides of the Same Coin? Independence and accountability of the European Central Bank, Transparency International.

- BVerfG, PSPP. (2020) Bundesverfassungsgericht, Judgment of 5 May 2020 – 2 BvR 859/15 et al., BVerfGE 154, 17.

- CJEU (2015). Court of Justice of the EU, Judgment of 16 June 2015 – C-62/14.

- Claeys, G., Goncalves Raposo, I. (2018). Is the ECB collateral framework compromising the safe-asset status of euro-area sovereign bonds?. Bruegel Blog Post.

- Cœuré, B. (2015). Embarking on public sector asset purchases, speech at the Second International Conference on Sovereign Bond Markets, Frankfurt, 10 March 2015.

- Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS). (2011). Interactions of sovereign debt management with monetary conditions and financial stability: Lessons and implications for central banks (CGFS Paper No. 42). Bank for International Settlements.

- Corradin, S., Grimm, N., and Schwaab, B. (2021). Euro area sovereign bond risk premia during the Covid-19 pandemic. ECB Working Paper No 2561, May 2021.

- Curtin, D. (2017). ‘Accountable Independence’ of the European Central Bank: Seeing the Logics of Transparency. European Law Journal 23(1–2): 28.

- Dawson, M., Maricut-Akbik, A., and Bobić, A. (2019). Reconciling Independence and accountability at the European Central Bank: The false promise of Proceduralism. Eur Law J. 25: 75–93.

- De Grauwe, P. (2011). The Governance of a Fragile Eurozone. CEPS Working Document No. 346, Centre for European Policy Studies, Brussels.

- De Guindos, L. (2025). Interview with Die Welt, of 17 September 2025.

- Deutsche Bundesbank (2022). Market conditions for Bunds in the context of monetary policy purchases and heightened uncertainty, Monthly Report 2022: 71.

- Draghi, M. and Trichet, J.-C. (2011). Letter to the Prime Minister of Italy, ECB, 5 August 2011.

- Draghi, M. (2018). Central Bank Independence. First Lamfalussy Lecture by Mario Draghi, President of the ECB, at the Banque Nationale de Belgique, Brussels, 26 October 2018.

- ECB 1998 Press Release, “A Stability-Oriented Monetary Policy Strategy for the ESCB”, (13 Oct. 1998).

- ECB (2003) Monthly Bulletin “The outcome of the ECB’s evaluation of its monetary policy strategy”, (June 2003), 79–92.

- ECB (2012). Technical features of Outright Monetary Transactions, Press Release of 6 September 2012.

- ECB (2012a). Box 1. Compliance of Outright Monetary Transactions with the Prohibition on Monetary Financing, in: ECB Monthly Bulletin 10/2012, 7–9.

- ECB (2015). ECB Response to letters (QZ-31 & QZ-32).

- ECB (2021). The ECB’s monetary policy strategy statement.

- ECB (2022). The Transmission Protection Instrument, Press Release of 21 July 2022.

- ECB (2023). Feedback on the input provided by the European Parliament as part of its resolution on the ECB’s Annual Report 2021.

- ECB (2025a). Asset Purchase Programmes.

- ECB (2025b). Accountability.

- ECB (2025c). ECB Response to EP letter QZ-015.

- ECB (2025d). ECB reviews risk control framework for monetary policy credit operations, Press Release.

- Economic Committee for the Study of Economic and Monetary Union. 1989. Report on Economic and Monetary Union in the European Community (Delors Report). Office for Official Publications of the E.C.

- European Parliament (2023). European Parliament resolution of 16 February 2023 on the European Central Bank – annual report 2022 (2022/2037(INI)).

- European Parliament (2025). Question for written answer Z-000015/2024 to the European Central Bank

- Fitch Ratings. (2022). Sovereign Rating Criteria. Fitch Ratings.

- Fendel, R. and Neugebauer, F. (2020). Country-specific euro area government bond yield reactions to ECB’s non-standard monetary policy program announcements. German Economic Review, 21(4): 417.

- Fromage, D., Dermine, P., Nicolaides, P., and Tuori, K. (2019). ECB independence and accountability today: Towards a (necessary) redefinition?. Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, 26(1): 3.

- Gabor, D. and Ban, C. (2016). Banking on bonds: The new links between states and markets. Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(3): 617.

- Geyer, A., S. Kossmeier, and S. Pichler. (2004). Empirical Analysis of European Government Yield Spreads. Review of Finance, vol. 1(2).

- Gorton, G.. 2017. ‘The History and Economics of Safe Assets’. Annual Review of Economics 9 (Volume 9, 2017): 547–86.

- Grauwe, P. de. 2014. Economics of Monetary Union. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press.

- Grünewald, S. and van ’t Klooster, J. (2023). New strategy, new accountability? The European Central Bank and the European Parliament after the strategy review, Common Market Law Review, 60 (4): 959.

- Hallerberg, M. and Wolff, G.B. (2008). Fiscal institutions, fiscal policy and sovereign risk premia in EMU. Public Choice, 136: 379.

- Heipertz, M, and Verdun A. (2010). Ruling Europe: The Politics of the Stability and Growth Pact. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Hinarejos, A. (2015). The Euro Area Crisis in Constitutional Perspective. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press.

- Högenauer, A., and Mendes, J. (2025). The ECB’s Evolving Mandate and High Independence: An Undemocratic Mix. Politics and Governance, 13, Article 9811.

- Hondroyiannis, G., and Papaoikonomou, D. (2022). The effect of Eurosystem asset purchase programmes on euro area sovereign bond yields during the COVID-19 pandemic. Empirical economics, 63(6): 2997.

- Ioannidis, M., Hlásková Murphy S.J., and Zilioli, C. (2021). The Mandate of the ECB: Legal Considerations in the ECB’s Monetary Policy Strategy Review. ECB.

- Issing, O. (1999). The Eurosystem: Transparent and Accountable or ‘Willem in Euroland’. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 37: 503-519.

- van ’t Klooster, J., and Fontan, C. (2020). The myth of market neutrality: A comparative study of the European Central Bank’s and the Swiss National Bank’s corporate security purchases. New political economy, 25(6): 865.

- van ’t Klooster, J. (2023). The Politics of the ECB’s Market-Based Approach to Government Debt. Socio-Economic Review 21(2): 1103.

- van ‘t Klooster, J. and de Boer, N. (2023). What to Do with the ECB’s Secondary Mandate. Journal of Common Market Studies, 6: 730.

- Krishnamurthy, A., and Vissing-Jorgensen, A. (2012). The Aggregate Demand for Treasury Debt. Journal of Political Economy 120 (2): 233.

- Lastra, R. (1992). The Independence of the European System of Central Banks. Harvard International Law Journal 33(2): 475.

- Lengwiler, Y., and Orphanides, A. (2024). Collateral framework: liquidity premia and multiple equilibria. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 56(2-3): 489.

- Magnette, P. (2000). Towards ‘Accountable Independence’? Parliamentary Controls of the European Central Bank and the Rise of a New Democratic Model. European Law Journal. 6: 326.