Reforming the Electricity Market in Europe

Can Europe decarbonise power markets without renationalising them?

- 1 The European reform in summary

-

2

National implementation: a kaleidoscope of models

- 2.1 France: hybrid post-ARENH regulation

- 2.2 Germany: Massive industrial subsidies and transition gas

- 2.3 Spain-Portugal: Leaving the Iberian exception behind

- 2.4 Italy: Liberalisation and the end of regulated tariffs

- 2.5 Poland and Central and Eastern Europe: Sovereign nuclear power and massive State guarantees

- 2.6 Nordic Countries: Defending marginalism and flexibility through pricing

- 3 Structural Tensions and Outlook

- 4 Towards what kind of European electricity market ?

Executive Summary

The 2021–2023 energy crisis exposed weaknesses in Europe’s electricity market. Between 2021 and February 2022, spot prices skyrocketed (€900-1,000/MWh in France and Germany), generating a cumulative budgetary cost of more than €600 billion for the EU. In June 2024, the Commission adopted a ‘two-tier’ compromise: preserving marginal pricing on spot markets for operational efficiency, and generalising bidirectional Contracts for Differences (CfDs) from 2027 onwards for public support for low-carbon capacities. These contracts guarantee a stable price for producers, while avoiding excessive revenues in the event of shocks. The reform also facilitates long-term contracts between private actors (Power Purchase Agreements/PPAs), strengthens social tariffs and institutionalises crisis mechanisms.

National implementation of the reform is highly differentiated. While the European framework sets common principles, Member States retain wide discretion, resulting in heterogeneous national models. France is adopting a Universal Nuclear Payment (a progressive levy on EDF’s revenues redistributed to consumers) and Nuclear Production Allocation Contracts for energy-intensive industries. Germany directly subsidises the price of electricity for heavy industry. Meanwhile, the Scandinavian countries, pioneers of liberalisation, fiercely defend the marginalist model. Spain and Portugal stand out for their massive volume of renewable PPAs. Italy is radically liberalising, closing regulated tariffs and betting on pure competition, despite the risks to the sustainability of suppliers. Poland is taking a massive State interventionist approach, with direct support for nuclear reactor projects, an option likely to be used by other Eastern EU countries.

These divergences are creating tensions within the Energy Union. Whilst northern European countries defend marginalism as a virtue that creates optimal economic signals, southern Europe perceives extreme volatility as a dysfunction that generates precariousness and deindustrialisation. This divide intersects with the issue of industrial competitiveness, since subsidies could force a race for aid. The reform marks a rebalancing between market rules and public instruments, with a risk of increasing the fragmentation of the internal market. To avoid this, three critical levers must be mobilised: harmonisation of industrial aid, risk pooling via strengthened European financial instruments, and coordination of energy policies beyond market rules.

The stakes are high and extend beyond electricity markets. The ability to increase electricity use in Europe is essential, not only for environmental reasons, but also to reduce dependence on fossil fuel imports, which, between Russia, the Middle East and the United States, are dominated by geopolitical considerations as much as economic ones.

1. The European reform in summary

1.1. From crisis to reform: a timeline

The energy crisis began in the summer of 2021, with the post-Covid recovery creating unprecedented tension in the liquefied natural gas (LNG) market, as Asia absorbed a large share of available shipments. As Russia gradually reduced its gas flows, European prices (TTF) jumped from €15/MWh at the beginning of 2021 to over €100/MWh in December. The invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 triggered a surge: the TTF reached €350/MWh in August, with electricity prices exceeding €900/MWh in France and €1,000/MWh in Germany at certain times[1].

This surge can be explained by the gas-electricity correlation due to the marginal cost pricing principle: the price of electricity is set by the cost of the most expensive producer called upon to meet demand at any given moment, generally gas, with a knock-on effect on electricity in the event of a shock. Other producers (nuclear, hydroelectric, renewables), known as ‘sub-marginal’ because their costs are lower than those of gas, benefit from huge profits in times of crisis: in France, EDF would theoretically have earned nearly €40 billion in 2022 without State regulation. In Spain, renewable producers have raked in more than €10 billion in profits, requiring the introduction of a special tax.

In this context, faced with the threat of social and industrial collapse, European States have deployed tariff shields, taxes on inframarginal rents and direct aids. The cumulative budgetary cost for the EU exceeded €600 billion over 2021-2023, making structural reform a matter of urgency[2].

1.2. The architecture of the reform: the ‘two-tier’ compromise

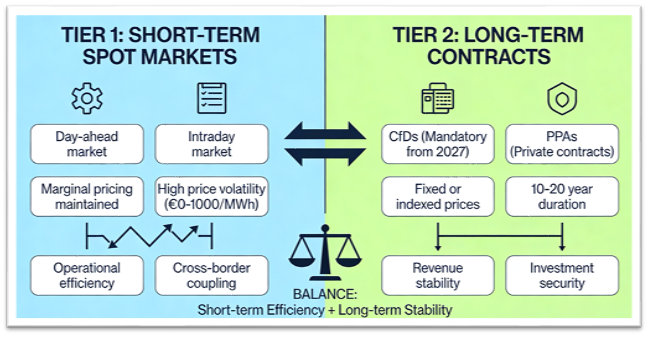

After intense consultations, the European Commission published a reform proposal on 14 March 2023, favouring a middle ground between two extremes: on the one hand, calls for a structural decoupling of electricity and gas prices (France, Spain, Greece, etc.) and, on the other, defence of the marginalist status quo (Germany, the Netherlands, the Nordic countries, Luxembourg, etc.). The compromise adopted in June 2024 preserves marginalism while generalising long-term instruments[3].

Maintenance of spot marginalism: Very short-term markets (day-ahead and intraday) retain the marginal price principle, which is considered essential for operational efficiency and cross-border electricity coupling. The argument for maintaining this system is that other methods (in particular pricing based on average costs) would have created inefficiencies or opacity[4].

Generalisation of Contracts for Difference (CfDs): From 2027 onwards, public support for low-carbon capacity will have to go through two-way CfDs5[5]. These contracts guarantee the producer a stable price, but oblige them to pay back any surplus to the State when market prices exceed this threshold. CfDs are therefore mechanisms for symmetrical risk and revenue sharing[6].

Facilitation of Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs): These PPAs are long-term electricity sales contracts between a producer and a buyer (company, supplier, aggregator, sometimes a local authority). In this contract, the parties set in advance the duration (often 5 to 15 years), the volume of electricity to be delivered, the pricing method (fixed, indexed, or formula-based), the delivery and billing terms, and the penalties for non-compliance. States must remove barriers to long-term PPAs through public guarantees and contract standardisation.

Consumer protection: The reform strengthens social tariffs, requires suppliers to offer fixed-price contracts, and institutionalises a crisis mechanism allowing for temporary interventions.

Figure 1 – The reformed “Two-Tier” architecture of the European electricity market

1.3. The structural limitations of the marginalist model in the transition

The crisis has revealed three structural flaws in marginal cost pricing in the face of the energy transition.

Decoupling average cost from marginal cost: Renewables have a marginal cost of almost zero (wind and sun determine production), but a significant average cost (due to high initial investment), whereas nuclear energy has fairly comparable characteristics. As a result, in a low-carbon electricity system, spot prices tend towards zero during periods of high renewable production, creating a problematic bimodality (periods of zero or negative prices alternating with periods of very high prices). This configuration makes the return on low-carbon investments uncertain and exposes consumers to volatility[7].

Faulty investment signal: For capital-intensive assets (nuclear at a minimum of €10 billion, offshore wind at €3-4 billion), the spot price is too volatile to trigger investment decisions. And liquid futures markets do not exceed a 3-4 year horizon, whereas these projects require revenue guarantees over 20-40 years.

Illegitimate sub-marginal rents: When prices explode for exogenous reasons (such as a geopolitical shock on fossil fuel markets), sub-marginal producers are in a position to capture arbitrary and politically unacceptable rents. These massive rents have forced governments to intervene in 2022, revealing the limits of pure marginalism in uncertain times[8].

2. National implementation: a kaleidoscope of models

The 2024 European reform establishes a common legal framework, but leaves Member States considerable leeway in its implementation. This latitude can be explained by three structural factors.

First, the principle of subsidiarity: Regulation (EU) 2024/1747 sets out general obligations (generalisation of CfDs for new investments, facilitation of PPAs, enhanced consumer protection), but does not prescribe the precise technical modalities. Member States remain free to set the strike prices for CfDs, the mechanisms for redistributing excess revenues, the eligibility criteria for industrial aid, and the levels of social tariffs.

Secondly, the diversity of energy mixes: The starting points are radically different. France has more than 300 TWh/year of historic nuclear power that has been amortised. Germany, which phased out nuclear power in April 2023, must compensate for 4.3 GW of controllable capacity while managing the loss of cheap Russian gas. The Nordic countries rely on an already largely decarbonised mix (hydropower, nuclear, wind) with dense interconnections. Each country adapts the European framework to its own geophysical and technological constraints.

Thirdly, divergent political orientations on the role of the State: Beyond technical constraints, national strategies reflect contrasting political philosophies. The Nordic countries favour minimal interventionism, rejecting any permanent regulated tariffs and limiting aid to targeted social safety nets. Conversely, France and the southern countries advocate active regulation to guarantee tariff stability as a public good. Germany is pursuing massive fiscal interventionism to preserve its industrial competitiveness. Poland is betting on sovereign nuclear power with unprecedented State guarantees. Italy has opted for radical liberalisation, abolishing regulated tariffs and betting on pure competition.

Six national models are emerging, forming a mosaic that calls into question the very future of the internal electricity market. This diversity can be seen as a wealth of experimentation that will help identify best practices, or as a threat of fragmentation that will create distortions of competition and a damaging race for subsidies. The following comparative analysis aims to map these differences, identify the underlying logic, and assess their implications for the cohesion of the European market[9].

2.1. France: hybrid post-ARENH regulation

End of ARENH and the need for transition

Regulated Access to Historical Nuclear Electricity (ARENH), established by the NOME law of 2010, ended on 31st December 2025. This mechanism required EDF to sell up to 100 TWh/year of nuclear production to alternative suppliers at an advantageous price (€42 then €46/MWh). The 2021-2023 crisis revealed the limitations of this mechanism: with spot prices exceeding €200/MWh on average in 2022, ARENH at €46/MWh represented a massive transfer.

Three factors led to the abandonment of ARENH: (1) incompatibility with EDF’s investment needs (major refits estimated to more than €50 billion, six new EPRs at €85 billion); (2) redistributive inefficiency, with some suppliers capturing the rent without passing it on to customers; (3) European pressure, with Brussels demanding a mechanism compatible with market design reform[10].

The post-ARENH triptych

The French government has developed a replacement system based on three complementary pillars:

Pillar 1: The Universal Nuclear Payment (VNU)

The VNU is a mechanism for progressively levying a tax on EDF’s historic nuclear revenues, which is then redistributed to all end consumers.

- Scope: All production from the historic nuclear fleet (reactors built before 2000), i.e. approximately 300 TWh/year.

- Market sales: EDF sells all its nuclear production on wholesale markets at market prices, with no regulated price obligations.

- Progressive levy: Each quarter, if the average selling price obtained by EDF exceeds defined thresholds, EDF returns to the State an increasing fraction of the excess revenue:

- Threshold 1: €78/MWh. Above this threshold, EDF pays back 50% of the difference.

- Threshold 2: €110/MWh. Above this threshold, EDF pays back 90% of the difference.

- Redistribution: The sums collected are redistributed to end consumers in the form of reductions on their bills, applied by all suppliers. The energy regulator (CRE) calculates the amount of the reduction in €/MWh each quarter.

Economic rationale: Unlike the ARENH, which set a sale price ex ante, the VNU operates ex post: EDF sells at market price, but pays back an increasing share of the revenue generated. This allows EDF to benefit from moderate increases (between €60 and €78/MWh, EDF keeps everything) while protecting consumers from extreme spikes (above €110/MWh, EDF keeps only 10% of the surplus).

Pillar 2: Nuclear Production Allocation Contracts (CAPN)

CAPNs are long-term contracts reserved for electricity-intensive industries.

- Eligibility: companies whose annual electricity consumption exceeds 7 GWh and whose electricity represents more than 30% of their production costs (heavy chemicals, steel, aluminium, glass, cement, data centres, electrolysis, etc.).

- Volume: Approximately 10 TWh/year reserved for CAPNs.

- Price: Negotiated bilaterally between EDF and each industrial company, but regulated by the CRE. Estimates around €65-70/MWh, stable over 10-15 years.

- Counterparties: Decarbonisation commitments (electrification investments, emissions reduction) and volume risk-sharing clause.

Economic rationale: To prevent the relocation of electricity-intensive industries to countries offering lower prices. However, this mechanism creates segmentation: eligible industrialists benefit from an advantageous regulated price, while SMEs and mid-cap companies face the spot market or the ex-post VNU.

Pillar 3: A safety net via an implicit CfD?

Although not explicitly formalised in public documents, it will be difficult not to implement protection for EDF against a sustained collapse in prices. In this scenario, if prices fell structurally below €60-65/MWh, the State would compensate EDF to cover the full cost of nuclear power. This implicit CfD is not a formal contract as it stands (as with Hinkley Point C, the British EPR project), but a last-resort insurance that the State shareholder will probably not be able to avoid, given the stakes involved, and EDF’s obvious status as too big to fail[11].

Issues and debates

Debate on the reference price for nuclear power: The CRE estimates the full cost of historical nuclear power at around €60/MWh, but EDF argues that the major refit will cost more and that the opportunity cost of capital must be included in the full cost assessment[12].

CAPN and fairness: CAPNs create an implicit subsidy for electricity-intensive activities. If the market price is €90/MWh and CAPNs are €65/MWh, manufacturers benefit from a €25/MWh advantage. Economically, this is a transfer from residential consumers to industry. Is this justified? There are three conflicting arguments: (1) Competitiveness (without CAPN, relocations and job losses); (2) Horizontal equity (why does the steelworks pay €65/MWh and the industrial bakery €120/MWh?); (3) Energy transition (CAPNs impose decarbonisation commitments, functioning as legitimate conditional subsidies).

2.2. Germany: Massive industrial subsidies and transition gas

Context: double shock from nuclear and gas

Germany completed its nuclear phase-out (Atomausstieg) on 15 April 2023, closing its last three reactors (Isar 2, Neckarwestheim 2, Emsland), leaving a gap of 4.3 GW of controllable capacity. At the same time, Germany had to replace Russian gas (~50 Gm³/year) from 2022 onwards. The accelerated construction of LNG terminals has enabled diversification, but the price of gas has risen from €15-20/MWh (2015-2020) to €30-40/MWh (average 2023-2024)[13].

This dual transition has created a major competitiveness shock. German manufacturing (20% of GDP) is particularly exposed. The chemical (BASF, Covestro, Evonik), steel (ThyssenKrupp, Salzgitter) and glass industries have seen their costs skyrocket. In 2022-2023, several chemical plants reduced their production by 30-50%, with some closing permanently to relocate to the United States.

The Strompreispaket: tax relief and direct subsidies

Faced with the risk of deindustrialisation, in 2024 the government adopted an ‘electricity price package’ (Strompreispaket), financed by the Climate and Transformation Fund (KTF), which is fed by EU ETS revenues and non-regular debt borrowing (partially circumventing the constitutional debt brake)[14].

The Strompreispaket combines three components:

Part 1: Drastic reduction in the Stromsteuer (electricity tax). The electricity tax was 1.5 ct/kWh. The Strompreispaket reduces it to the European minimum of 0.05 ct/kWh for the entire manufacturing sector from 2024, reducing the total price for industry by 15-20%.

Part 2: Extended compensation for indirect CO₂ costs. Energy-intensive industries must pay for the CO₂ incorporated into electricity. To avoid losing competitiveness, Germany compensates around 350 particularly energy-intensive companies for this additional cost. The Strompreispaket extends this compensation, with an annual budgetary cost of €2-3 billion.

Part 3: Direct subsidy. For the most intensive companies (steel, primary chemicals, aluminium, electrolysis), the government is targeting a price of €50-60/MWh for 2026-2028. If the market price is 120, the State will pay a direct subsidy of at least 50% per MWh consumed, subject to a cap per company.

Notified to the Commission as temporary State aid, Brussels approved it in November 2024 subject to conditions: limitation to three years, conditionality on green investments (electrification, green H₂, CO₂ capture), and total transparency[15].

Hydrogen-ready gas-fired power plants: a technological gamble or fossil fuel lock-in?

Berlin is launching a programme to build 8-10 GW of flexible gas-fired power plants, described as ‘hydrogen-ready’. The idea is to build CCGT plants running on natural gas (2025-2030), then switch to green hydrogen (2030-2040) as it becomes available.

Strategic rationale: Germany is aiming for 80% renewables by 2030, and managing intermittency requires flexible back-up capacity for ‘Dunkelflauten’ (periods without wind or sun). In the long term, these power plants would switch to green hydrogen, completely decarbonising the back-up.

Criticisms: NGOs see this as a risky technological gamble and a disguised fossil fuel lock-in. The risk is that once built, gas-fired power plants will never switch to H₂ (too expensive or unavailable) and will continue to burn fossil gas until 2050, hindering climate goals. Other options would involve a massive increase in battery storage (50-100 GW by 2035), the development of demand response and increased interconnections (allowing greater access to Norwegian hydropower, French nuclear power, Spanish solar power, etc.).

2.3. Spain-Portugal: Leaving the Iberian exception behind

The Iberian exception: mechanism and results

The ‘Iberian exception’, approved in June 2022, allowed Spain and Portugal to cap the price of gas used for electricity generation in day-ahead markets. The mechanism consisted of limiting thermal generation bids to reduce the marginal price. Consumers paid a lower price for the electricity consumed plus compensation to gas producers, with the total cost theoretically lower due to volume (the gas surcharge only applies to gas-fired electricity, not to all generation). The overall result is mixed.

Positive effects:

- Consumer protection: Before the exception, average Spanish prices were €214/MWh at the beginning of 2022. After it came into force, the final price passed on to consumers was 57% lower than the European average in the second half of 2022 and 28% lower in 2023.

- Estimated savings: Approximately €5 billion for Spanish consumers over 18 months.

- Confirmation of concept: The experiment established that partial gas-electricity unbundling was technically feasible.

Negative effects and limitations:

- Increase in the share of gas: The gas subsidy encouraged an increase in thermal production, with the share of gas in the mix rising from ~15% to ~30%.

- Administrative complexity: Cumbersome management of compensation to producers.

- Subsidies for French exports: Through interconnections (limited to 3% of Spanish capacity), France partially benefited from the mechanism.

- Diminishing marginal effect: From February 2023 onwards, the mechanism no longer had any effect on market prices (as gas prices had fallen), but continued for domestic policy reasons.

The European Commission refused to extend it beyond December 2023, considering that prices had stabilised and that the exceptional mechanism was no longer justified.

Transition to the European model

Since January 2024, Spain and Portugal have been converging towards the European reference model, with two main pillars.

Acceleration of renewable PPAs: Spain is the European leader in PPAs. Large companies (GAFAM, electricity-intensive manufacturers) are signing long-term PPAs (10-15 years) with renewable producers on a massive scale, securing prices and green supply[16]. Several dozen GW have been under PPA since 2024, far exceeding the European average observed elsewhere.

CfD tenders for new capacity: Spain is rolling out competitive tenders for onshore wind, solar photovoltaic and offshore wind. Producers bid strike prices with the cheapest being selected and awarded bidirectional CfDs for 15-20 years.

The experience has fuelled the European debate on market design reform. Spain advocated a structural mechanism for decoupling electricity and gas prices, inspired by the Iberian exception but generalised to the EU. However, Brussels refused, favouring the dissemination of CfDs and PPAs.

2.4. Italy: Liberalisation and the end of regulated tariffs

End of the Mercato di Maggior Tutela: radical liberalisation

Italy has opted for radical liberalisation of the retail market, permanently ending regulated tariffs (Mercato di Maggior Tutela): gas in January 2024, electricity in April 2024. Until that date, residential consumers and micro-enterprises could choose between the free market and the regulated tariff, where the price of energy was set by the regulatory authority ARERA.

Consumers who did not choose an offer on the free market before the deadline (approximately 20% of the market, or ~4.5 million electricity customers) were transferred to the Graduated Protection Service (Servizio a Tutele Graduali). This service replaces the regulated tariff, which is now only available to vulnerable customers. It serves as a transitional option for a maximum of three years or until customers choose a market offer.

The contractual conditions and tariff structure of this service are determined by the regulatory authority, with the electricity price based on the wholesale price (PUN, Prezzo Unico Nazionale). Customers previously on the regulated tariff have been assigned to a single supplier per regional zone through reverse auctions. Suppliers bid for a discount on the current regulated tariff, to be applied for three years to the customers acquired.

The discounts obtained through this mechanism are substantial: on average, each consumer will save around €130 per year compared to the regulated tariff, with savings of around €1.8 billion expected. According to DFC Economics, which assisted ARERA in designing the auction: ‘The auctions held in Italy in 2024 provide reassuring evidence that consumer aggregation and competitive bidding can offer an effective means of delivering the benefits of competition to all electricity consumers’.

Strategy and risks of full liberalisation

Italy is betting that competition between suppliers will benefit consumers and stimulate innovation. Full liberalisation, in line with Directive (EU) 2019/944, aims to:

- Create competitive pressure forcing suppliers to optimise their offers.

- Stimulate innovation (green offers, dynamic contracts, additional services).

- Align Italy with more mature markets (UK, Nordic countries).

But, multiple identified risks must be underlined:

- A ‘British-style’ retail market crisis: The United Kingdom saw more than 30 suppliers go bankrupt in 2021-2022, unable to cope with extreme wholesale price volatility. By removing the safety net of regulated tariffs, Italy is exposing consumers to the same risk.

- High prices and volatility: Italian wholesale prices have soared in 2022 due to dependence on gas (Italy imports ~40% of its energy) and network bottlenecks.

- Zonal pricing and regional inequalities: Italy introduced zonal pricing in 2025 (replacing the single PUN). This creates price differentials between regions, penalising the South (which has a deficit) in favour of the North (which has a surplus).

- Complexity for vulnerable consumers: Elderly or low-income households, unfamiliar with competitive markets, risk being offered unfavourable deals or remaining passively on the Protection Service.

Italy’s liberalisation is testing the market’s ability to self-regulate an essential sector. If competition effectively delivers low prices and innovation, Italy will validate the pure liberal model. If it replicates the British crises (bankruptcies, price spikes), it will fuel criticism of the model and could force a partial return to regulation.

2.5. Poland and Central and Eastern Europe: Sovereign nuclear power and massive State guarantees

The Polish nuclear programme: an unprecedented financial architecture

In November 2022, Poland selected Westinghouse AP1000 technology to build three reactors at the Lubiatowo-Kopalino site in Pomerania (northern Poland). A development agreement was signed in May 2023 between Westinghouse, Bechtel, and Polskie Elektrownie Jądrowe (PEJ), a special purpose vehicle wholly owned by the Polish Treasury. The total cost of the project is estimated at €45-50 billion for three AP1000 reactors (total capacity ~3.7 GW).

In September 2024, the Polish government notified the European Commission of its intention to support this investment through a substantial state aid package:

- Public capital injection: Approximately €14 billion, covering 30% of the project costs.

- State guarantees: 100% coverage of the debt incurred by PEJ to finance the project.

- Bidirectional Contract for Difference (CfD): Providing income stability over the entire lifetime of the plant (initially 60 years, ultimately reduced to 40 years after negotiations with Brussels).

European validation and conditions imposed

On 8 December 2025, the European Commission approved the State aid package, concluding that it complies with EU rules. According to the Commission: ‘This is one of the largest, if not the largest, individual State aid measures in the history of the European Union’[17].

However, to ensure that the aid is appropriate, proportionate and does not unduly distort competition, Poland had to agree to several significant adjustments:

- Reduction in the duration of the CfD: From 60 years initially to 40 years, aligned with the debt repayment cycle.

- Revision of the CfD design: Ensuring strong incentives for PEJ to operate the plant efficiently and respond to market signals. The revised CfD includes: (i) Integration of long-term markets (PPAs, forwards) into the settlement system; (ii) The ability to adjust production flexibly, when economically and technically justified; (iii) Windfall profit sharing mechanism: Windfall profits, when they occur, will be allocated directly to the State budget and will finance public expenditure.

- Obligation to sell on the open market: To mitigate the risks of market concentration and prevent aid from being passed on to consumers in an opaque manner, Poland has committed to selling at least 70% of the power plant’s annual electricity production on the open electricity exchange (day-ahead, intraday and futures markets) throughout the plant’s lifetime. The remaining 30% may be sold through auctions conducted under objective, transparent and non-discriminatory conditions.

- Legal and functional independence of PEJ: Poland has committed to ensuring that PEJ is legally and functionally independent from other major operators in the Polish electricity market, in order to avoid conflicts of interest and anti-competitive practices.

A model that can be replicated in Central and Eastern Europe?

The Polish case illustrates the return of massive State interventionism for strategic decarbonisation infrastructure. Several countries in Central and Eastern Europe (the Czech Republic, Romania, Bulgaria and Slovakia) are considering nuclear programmes that include State guarantees.

Common features of the model:

- The State as the lender of last resort: Direct public capital (30% in Poland), 100% sovereign guarantees on debt.

- Very long-term CfDs (40-60 years) to secure revenues and enable bank financing.

- Strong conditionality: Mandatory sale on the open market (minimum 70%), exceptional profit-sharing mechanism, operator independence.

This model marks a break with the neoliberal doctrine of the 2000s: the State becomes the direct sponsor of massive projects, assuming the construction and operating risks that the private sector refuses to bear alone. Brussels’ approval sets a precedent: other states can now apply for similar State aid for nuclear projects, subject to compliance with EU conditions (aid limitation, obligation to sell on the open market, control of anti-competitive effects).

Marek Woszczyk, Chairman of the Board of PEJ, said: ‘The Commission’s final decision approving State aid – one of the largest, if not the largest, individual aid package in the history of the EU – within this timeframe and in this form is a huge success for the Polish side and an example of exemplary cooperation between the administration and a public company’.

2.6. Nordic Countries: Defending marginalism and flexibility through pricing

Nord Pool and the established market culture

The Nordic countries (Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark) are pioneers of liberalisation: Nord Pool was created in 1992, becoming the largest coupled market in Europe (more than 1,000 TWh/year). For thirty years, the marginalist model worked satisfactorily: spot prices effectively guided investments (new hydroelectric power plants, Norway-Denmark-Sweden interconnections), and Nordic consumers gradually adapted to volatility through flexible contracts, smart equipment (modular heating), and an established market culture[18].

Characteristics of the model:

- Already largely decarbonised mix: Norwegian hydro, Finnish nuclear (+ new Olkiluoto 3 reactor in 2023), Danish wind.

- Dense interconnections: Enabling massive exchanges between countries (Norwegian hydro exports to Sweden/Denmark, Finnish nuclear imports from Sweden).

- Multiple price zones: Sweden has four zones and Norway has five, reflecting physical congestion in the grid.

- Acceptance of volatility: Nordic consumers, exposed to spot prices or indexed contracts, adjust their consumption according to prices (adjustable electric heating, EV charging during off-peak hours).

Opposition to intervention and defence of price signals

The Nordic countries were the most vocal opponents of French and Spanish calls for radical market reform in 2022-2023. Their position is based on the argument that volatility is not a dysfunction, but a desirable feature that sends essential economic signals:

- Signal of operational efficiency: When electricity is expensive (high demand, low renewable production), consumers and producers must respond by reducing consumption or activating flexible capacity.

- Incentive to invest in flexibility: Volatile prices encourage investment in storage (batteries, pumped hydro), demand response and interconnections.

- Avoiding distortions: Capping prices or decoupling electricity and gas would send the wrong signals, discouraging the investments needed for the transition.

Price zones: debate on optimal segmentation

The issue of bidding zone segmentation is crucial for the Nordic countries. Sweden, divided into four zones since 2011, is experiencing massive price differences: in 2022-2023, the difference between SE1 (North, with a surplus of hydroelectric power) and SE4 (South, including Stockholm, with a deficit) regularly exceeded €100/MWh[19] :

- Southern politicians calling for re-segmentation (creating even more zones to refine local prices and reduce prices in SE4).

- Elected officials in the North want to merge zones (to dilute high prices in the South and prevent the North from subsidising the South through low prices).

- Producers in the North benefit from low prices in SE1, reducing their revenues, while producers in the South capture high prices.

The European Commission mandates ACER to periodically review the zones, but each review is a distributive conflict in which massive revenues are distributed among territories.

The Nordic countries have reluctantly accepted the generalisation of CfDs for new investments, seeing it as a necessary evil to achieve European consensus. But they categorically refuse:

- The extension of CfDs to existing assets (as requested by France and Spain).

- Mechanisms for permanently capping spot prices.

- The creation of separate markets by technology (nuclear, renewables, gas).

Their preference remains for minimal interventionism: highly targeted social safety nets (aid to the poorest 10-15% households), social tariffs for vulnerable consumers, but no permanent regulated tariffs or universal redistribution mechanisms.

3. Structural Tensions and Outlook

3.1. Market prices versus political prices: philosophies of regulation

A major ideological divide runs through Europe on the issue of the legitimacy of price volatility.

Nordic view: volatility as a virtue. Nordic countries argue that volatile prices send essential economic signals: when electricity is expensive, consumers and producers must react. This philosophy is rooted in thirty years of positive experience with the marginalist pricing model. Nordic consumers have adapted through flexible contracts and smart equipment.

Southern European vision: volatility as dysfunction. Southern countries (Spain, Portugal, Italy, Greece) and France perceive the extreme volatility of 2021-2023 as an unacceptable dysfunction creating energy insecurity, deindustrialisation and social division. From this perspective, price stability is a public good that the State must preserve. Electricity prices, which affect all citizens and businesses, cannot be left solely to the logic of short-term supply and demand.

This divergence is reflected in opposing institutional choices: the Nordic countries reject any permanent regulated tariffs and limit interventions to targeted social safety nets; the South and France maintain regulated tariffs or universal redistribution mechanisms (French VNU, Spanish shields).

3.2. Industrial competitiveness versus budgetary discipline

How can we reconcile the preservation of Europe’s industrial base in the face of American and Chinese subsidies with the fiscal sustainability of Member States?

Germany has opted for competitiveness, mobilising close to €30 billion, in three years, to subsidise industrial prices. France is seeking a middle ground by socialising nuclear rents via the VNU rather than creating a direct budgetary subsidy. Poland is taking a highly interventionist approach (€14 billion capital injection, 100% debt guarantees) for nuclear power.

But countries with tight budget margins (Italy, Spain, CEECs) fear a destructive fragmentation of the internal market: if each State pays different amounts of subsidies, investment will be concentrated in the most generous countries, creating a race for aid that could be damaging to all[20].

3.3. Transition investment versus social justice

The energy transition requires massive investment: the European Commission estimates that €380-400 billion per year will be needed between now and 2030 to achieve the 55% emissions reduction target. How can this increase be financed without exacerbating social inequalities?

Sustainably higher electricity prices would be economically justified (they reflect the real cost of decarbonisation and encourage adaptation investments), but politically explosive. Hence the use of temporary price caps (cumulative cost of more than €600 billion in Europe in 2021-2023), social tariffs, and redistribution mechanisms such as the French VNU or Italian auctions.

But in the long term, are these budgetary transfers sustainable? Should we accept price increases for certain segments of the population, at the risk of creating social divisions? This tension between economic efficiency and distributive equity runs through all national debates.

4. Towards what kind of European electricity market ?

The 2024 market design reform marks a decisive but not conclusive step in the evolution of the European energy model. It confirms the exhaustion of the neoliberal paradigm of the 1990s, based on the belief that liberalisation and competition would be sufficient to organise the electricity sector efficiently. The massive return of the State – as a financier (CfD, guarantees), regulator (French VNU, German industrial prices) and planner – reflects a growing awareness that the energy transition cannot be achieved by the market alone.

But this repoliticisation of energy also opens up a major risk of fragmentation. If each Member State interprets the European framework according to its immediate interests, multiplying national interventions (industrial subsidies, taxes on rents, regulated tariffs), the internal market could dissolve into a patchwork of poorly coordinated regimes. The winners would be the richest or most influential countries (Germany, France, Nordic countries), while countries in the South and East would have less room for manoeuvre.

4.1. Two polar scenarios on the horizon

Scenario 1: harmonisation through soft convergence. Bidirectional contracts for difference appear to be a quasi-universal tool for supporting low-carbon investments, gradually creating a common basis for practices. National differences (strike prices, contract duration, redistribution mechanisms) remain, but are part of a coherent framework. Minimal coordination of industry support, under the aegis of the Commission and the EIB, helps to avoid a destructive subsidy race. European instruments (structural funds, EIB guarantees) are strengthened in order to pool risks and support states with tight budgetary margins.

Scenario 2: fragmentation and renationalisation. National differences are becoming more pronounced, with each Member State adjusting European rules to protect its immediate interests. Germany and the rich countries are increasing industrial subsidies, forcing their neighbours to respond in a race for aid. The countries of the South and East, unable to keep up financially, are seeing their industries relocate to the North. The internal electricity market formally remains in place (spot market coupling), but its effectiveness is eroded by a proliferation of disorderly national interventions. The promise of an efficient single market, a pillar of the European project since the 1990s, fades in favour of a mosaic of poorly coordinated national regimes.

4.2. Three levers to avoid fragmentation

To avoid the risk of fragmentation, three levers could be activated:

- Minimum harmonisation of industrial aid: The Commission and the Council must mitigate the race for subsidies. While the Clean Industrial Deal State Aid Framework (CISAF) adopted in June 2025 provides a legal basis for operating aid to electro-intensive industries, it lacks explicit mechanisms to prevent destructive fiscal competition between Member States. To mitigate this disparity, the Commission should monitor and publish comparative subsidy intensity by sector and country under CISAF, and link complementary instruments (ECF, EIB guarantees) as a mechanism for regulating distortions.

- Risk pooling via European financial instruments: The European Competitiveness Fund (ECF), currently negotiated as part of the next multiannual financial framework 2028-2034, should provide guarantees for CfDs and PPAs. However, the critical policy question is adequacy of scale. Negotiators should ensure guarantee allocations are sufficient to prevent a two-speed transition – with capital-rich countries deploying CfDs rapidly and financially constrained countries rationing investment due to fiscal limits. The European Investment Bank’s 2025 pilot programme for corporate PPA guarantees (launched to accelerate renewable PPAs among SMEs and mid-cap companies across the EU) provides a proof-of-concept that guarantee instruments effectively de-risk intermediaries and unlock private aggregation, and should be expanded.

- Improved coordination of energy policies: The energy transition requires coordinated investment across borders – renewable deployment, grid reinforcement, hydrogen infrastructure, and demand management cannot be optimally pursued by 27 countries in isolation. The recently proposed EU Grids Package attempts to institutionalise this through mandatory cross-border network planning, but so far faced opposition from several Member States. Beyond environmental issues, the international context requires this enhanced coordination with a view to sovereignty and economic efficiency.

The 2024 reform created the architecture. All that remains is to build the common house — or to accept a fragmented Europe where everyone builds their own isolated pavilion. The years 2025-2026, a period of national transposition of directives and initial feedback on the French VNU, German Strompreispaket and Polish CfD schemes, will be decisive in determining which path Europe will take.

About the author: Patrice Geoffron holds a PhD in industrial economics and is professor at Paris-Dauphine University, where he served as interim president and international vice-president. He is also the founding director of the Dauphine Economics Laboratory.

For the past twenty years, he has specialised in evaluating investments in environmental transition and, more recently, in adapting infrastructure to climate change. Among other responsibilities, he sits on the Scientific Council of the CEA, Engie and the CRE and is a member of the Cercle des Économistes. Previously, he was a member of the World Council of the International Association for Energy Economics and an expert for the Citizens’ Climate Convention.