Europe’s Trump Cards

Why the continent has more leverage than it thinks

Executive Summary

Raw power is not leverage. Conventional wisdom assumes that American material superiority leaves Europe with little room for manoeuvre. This paper disputes that view. Leverage arises from asymmetric dependencies — the capacity to impose costs without incurring proportional harm. Across macroeconomic ties, product dependencies, financial markets, digital infrastructure and energy, Europe holds more cards than commonly assumed.

Europe controls several strategic chokepoints. European suppliers provide around 80 percent of US uranium imports. Siemens dominates the medium-sized gas turbines needed for US data centres. The EU’s USD 10 trillion consumer market underpins US technology valuations and, by extension, American retirement savings. From 2027 onward, expanding global LNG capacity is projected to shift bargaining power toward buyers, strengthening Europe’s position.

The US position is more fragile than it appears. Demand for US Treasuries depends heavily on leveraged private actors, including London-based hedge funds. US technology valuations rely on continued access to European consumers. LNG exporters depend on Europe’s premium prices. The United States cannot fully retreat from global interdependence while continuing to benefit from it.

Europe’s challenge is not a lack of leverage but a lack of political readiness. The EU possesses instruments such as the Anti-Coercion Instrument and procurement tools that could raise the cost of economic pressure. Yet deploying them requires political decisions that create winners and losers across Member States. Without pre-negotiated burden-sharing arrangements, governments are likely to hesitate — and external actors are aware of this constraint.

Strategic coordination must precede crisis. If Europe wishes to use its leverage effectively, it must prepare institutional and political mechanisms in advance. Transparent burden-sharing arrangements and intergovernmental coordination — including cooperation with the United Kingdom — are essential. London remains central to financial markets, and exclusion would weaken Europe’s position.

Europe has more room to act than it believes. The United States holds greater material resources. But leverage depends on structure, not size. By understanding interdependencies and organising its response accordingly, Europe can reduce exposure and defend its interests in an unpredictable geopolitical environment.

Policy Recommendations

- Make the Anti-Coercion Instrument credible. Ensure it can be deployed decisively by clarifying procedures and underpinning it with political commitment.

- Expand priority procurement powers. Strengthen Europe’s ability to act collectively in areas where it controls strategic supply-chain chokepoints.

- Strengthen Europe’s digital position. Consolidate regulatory and market leverage to reduce asymmetric dependence in digital infrastructure and platforms.

- Treat the design of financial markets as geopolitical issues. Recognise that Treasury demand, repo markets and cross-border financial linkages shape strategic leverage.

- Build intergovernmental capacity that includes the United Kingdom. Develop structured cooperation recognising London’s systemic role in financial markets.

- Engage in transparent horse trading before crises, not during them. Pre-negotiate burden-sharing arrangements so that political hesitation does not undermine Europe’s credibility when leverage must be used.

1. Introduction

Europe is in a novel situation. Suddenly, it is being challenged by an increasingly unpredictable US President Donald Trump. Conventional wisdom holds that America’s material superiority—its economic scale, military dominance, and control over critical goods and global infrastructure—leaves Europe with little room for manoeuvre. We dispute this assessment. Europe has leverage, which it can use to defend its own interests and contribute to a stable world order.

The United States displays every marker of superpower status. Its military spending dwarfs that of any potential rival. Its economy is the world’s largest, its currency the lifeblood of international financial markets, its infrastructure the arteries of the global information system, its products the world’s most innovative and its goal of energy dominance is not far off. By any measure of material power, the US has far more chips than Europe.

Yet power and leverage are not the same thing. Power refers to absolute capabilities. Leverage describes the capacity to impose asymmetric costs—to hurt another actor without incurring proportionate harm yourself. Leverage arises not from sheer scale but from specific structural features of interdependence: chokepoints where control over a single node grants disproportionate influence; frictions that prevent rapid substitution; and systemic accelerants—network effects, proprietary technologies, and lock-in mechanisms that propagate shocks fast and wide.

Complete decoupling from the US is neither realistic nor desirable. The question is not whether Europe will remain connected—it will—but how to structure that relationship to protect against arbitrary interference. The relevant question is whether particular American companies, financial institutions, or government agencies can achieve their objectives without European participation—and whether European policymakers are willing to impose costs selectively. Leverage is not a blunt instrument; it’s a scalpel.

This paper first takes stock of how power is allocated and then examines European leverage across five dimensions—economic growth, product dependencies, financial markets, digital infrastructure, and energy. We omit defence, which is sufficiently covered elsewhere. Our work builds on Tobias Gehrke’s identification of European leverage points, which provides a comprehensive overview of available measures (Gehrke 2025). We focus on a narrower set of approaches and interrogate the political economy involved. This matters because material impact is what counts; geopolitics becomes deeply personal when employment is put at risk, the cost of living increases or retirement savings vanish.

We find that Europe possesses considerably more leverage than is commonly assumed. The question is not whether Europe can match American power—it cannot. The question is whether Europe can deploy its cards strategically enough to defend its interests. The answer is yes.

2. Superpower US

2.1. Sizing up material power

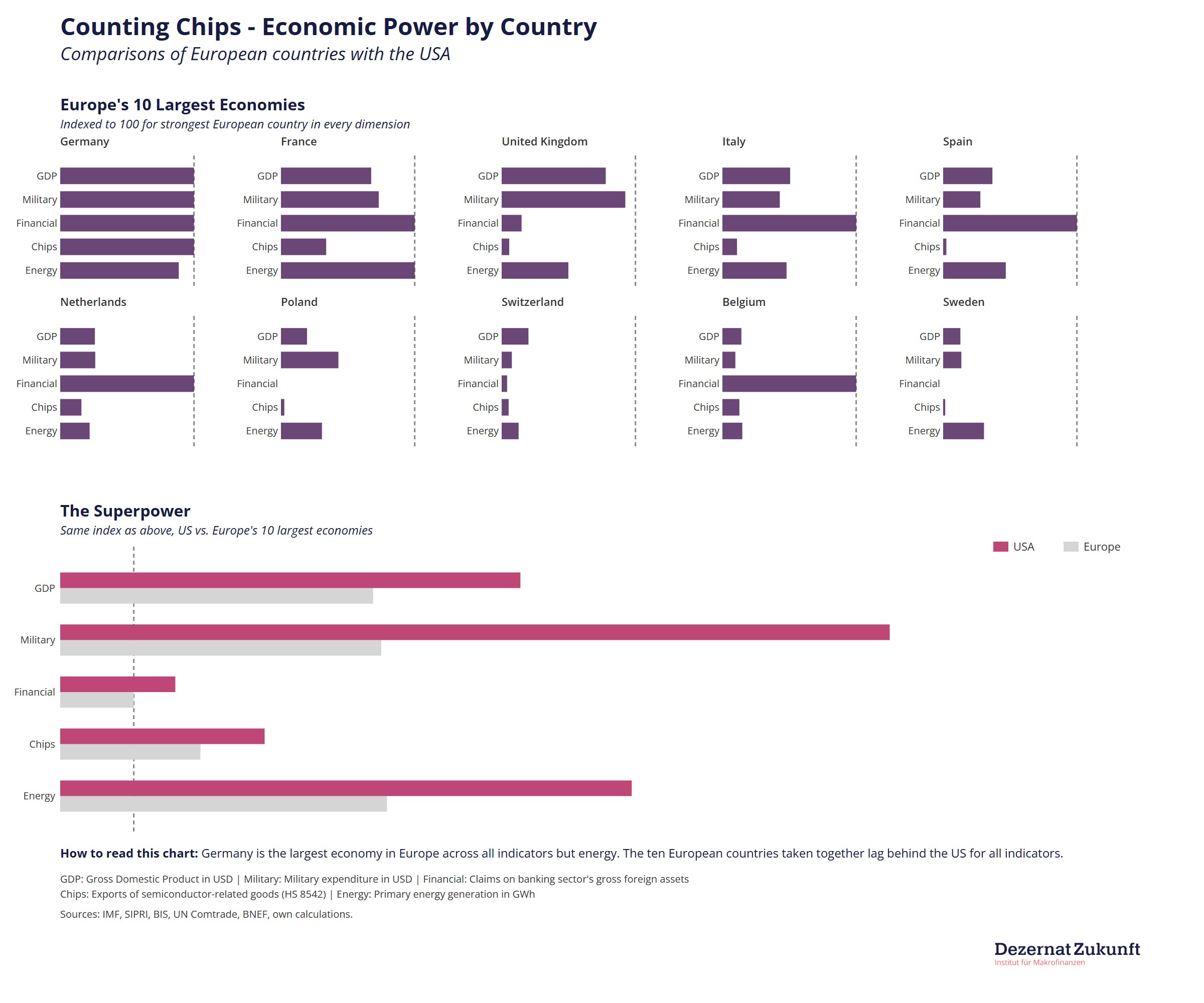

We consider material power along five dimensions: The size of the economy and defence expenditures, the ubiquity of one’s currency (through cross-border financial claims), semiconductor sales and energy production. Our power index shows a very simple and rough comparison of the pile of chips every country has. It is not supposed to provide an exact measure but give a sense of the starting position.

Figure 1: Indicators of Economic Power by Country

We draw three conclusions from this: First, the US is in a category of its own with all the markers of a superpower. Even the ten largest European economies combined cannot match the US’s chips. But, as closer inspection reveals, being a global superpower also means being exposed to global events.

Second, the UK is key for Europe. It has the second-largest GDP in Europe and the secondlargest defence expenditures. As we dive further into questions of leverage, the UK will become even more important given London’s role as the predominant financial centre of the world. Thus, it is in the EU’s own interest to collaborate with the UK regardless of Brexit.

Third, most importantly, power does not necessarily translate into specific leverage. You cannot threaten another country with your big GDP. What you can threaten the other country with is closing your big market to them or withholding your products that the other country may need. In the following sections, we trace how power translates into leverage.

3. European leverage

3.1. Macro leverage: The USD 10 trillion hostage

On the face of it, the US has just demonstrated its leverage as the dominant economy in stark terms. The July 2025 trade deal saw Europe commit to USD 750 billion in energy imports from the US and USD 600 billion in US investments over three years. Europe accepted a 15 percent baseline tariff on most exports and the continuation of 50 percent tariffs on steel and aluminium (Krahé et al. 2025). Germany, as Europe’s largest export economy, is suffering particularly badly: exports to the US fell 13.4 percent between April and November 2025, though total German exports barely moved as firms redirected to other markets (Statistisches Bundesamt 2025).

Yet on the whole, trade between the US and EU is fairly balanced; include services alongside goods and the EU’s headline surplus shrinks to just EUR 50 billion—less than 0.3 percent of EU GDP. More importantly, the US and the EU share a feature which ties their fate together: They are home to the world’s largest and wealthiest consumer markets.

US household consumption stands at nearly USD 21 trillion, the EU’s at USD 10 trillion—no other market comes close. China ranks third with USD 7.5 trillion, but spread across 1.4 billion people with far lower incomes. (International Monetary Fund 2025b; Eurostat 2024; OECD 2024; National Bureau of Statistics of China 2025). The US and EU consumer markets reflect a unique combination of population size, high GDP per capita, and comparatively low household savings. Americans spend roughly 95 percent of their disposable income, Europeans 92 percent. Chinese households, by contrast, spend only 68 percent—and start from a GDP per capita of just USD 14,000, a fraction of American or European levels (International Monetary Fund 2025b; Eurostat 2024; OECD 2024; National Bureau of Statistics of China 2025). As much as Europe needs the US, American consumerfacing businesses cannot do without the European market.

This matters enormously for the “Magnificent Seven” US technology companies. Revenue data for the European divisions of the Magnificent Seven is hard to come by but assuming Meta’s European share of 23 percent (Meta Platforms Inc. 2025) is representative, gives some indication of the order of magnitude: If Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, NVIDIA, and Tesla all made 23 percent of their sales in Europe, they would generate revenue exceeding USD 500 billion annually (S&P Capital IQ 2026). Even more than that: Their growth stories are predicated on selling in Europe. Otherwise it is impossible to justify their valuations with price-to-earnings multiples in the range of 30x and more (S&P Capital IQ 2026), premised on continued global growth. The S&P 500’s thirtyyear median P/E on reported earnings is 22x (S&P Dow Jones Indices 2026). If the Magnificent Seven were to lose access to the EU’s 450 million wealthy consumers, investors would probably not simply discount the lost revenue—they would re-rate the entire growth narrative. A compression from current multiples to 22x would imply 30 percent of loss in market value.

Such a stock market correction would not be an abstract financial event. It would propagate through society at great speed thanks to a systemic accelerant: 401(k) retirement accounts. Because 401(k) payouts depend on fund performance, and roughly one quarter of 401(k) contributions are invested in the Magnificent Seven, any tech crash would hit retirement incomes across the entire country (Capul 2025). State pension funds would suffer as well. Trump Accounts, launching in the summer of 2026, will deepen this exposure: the government will invest USD 1,000 in index funds for every child born since 2025—tying the next generation’s savings to Magnificent Seven performance from birth (U.S. Department of the Treasury 2026). Tech employees, whose compensation often includes stock, would see their wealth shrink. And political donors across the spectrum—many of them tech executives or investors—would feel the pain directly. Thus, the US is indeed heavily reliant on the European consumer market.

The US response to regulatory fines—not market exclusion—under the European Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act indicates that this analysis is correct: threats of retaliation against European companies have been made, Section 301 investigations initiated and a visa ban has been imposed on former Commissioner Thierry Breton. There have even been suggestions of linking NATO support to tech regulation (Lima-Strong 2025). Tech CEOs have explicitly called on the US government to “defend” them abroad (Duffy 2026). This is not the behaviour of companies with comfortable alternatives.

A full retreat of US tech giants from Europe remains hard to believe. Europeans need the products, and the US government will not want to put millions of Americans in despair by destroying their retirement savings. More likely is a localisation strategy, with European subsidiaries ring-fenced to satisfy regulators while preserving market access. Yet localisation has limits—US legislation like the CLOUD Act or extraterritorial sanctions applies regardless of where they operate. Europe should not grow complacent. Just because the US is unlikely to flip the kill switch Europe should not consider itself safe from coercion—US pressure in the digital sphere is routine, even if typically aimed at individual actors rather than systemic policy change. To counter it, Europe needs to strengthen its own position. We cover this in the section on digital leverage.

3.2. Product leverage: Turbines and uranium

Leverage is not just a macro question playing out in markets. As we have painfully learned during Covid, there is such a thing as chokepoints—central nodes of economic networks which can be weaponised by governments (Farrell and Newman 2019). Effective chokepoint leverage today mostly means gradual squeezing, not complete embargos—the latter risk being disproportionate or spurring alternatives. Such a gradual approach does not shut down supply chains; it increases costs and builds leverage when applied with discipline.

One prerequisite deserves attention before discussing individual products: the European mechanism for deciding on chokepoints. Until 2023 this was the main bottleneck for turning power into leverage for Europe. However, in December 2023, Regulation (EU) 2023/2675, establishing the Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI), entered into force. When activated, it empowers the European Commission to impose trade restrictions in response to economic coercion by third countries (Regulation (EU) 2023/2675 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 November 2023 on the Protection of the Union and Its Member States from Economic Coercion by Third Countries 2023). Europe thus has the legal framework in place to use product leverage. One may object that the ACI is a defensive tool. Yet it seems reasonable to assume that under any circumstances which may warrant its use, the preconditions will be fulfilled. Thus, it will provide leverage when needed. A more complex issue is the political economy behind the activation of the ACI, which we will discuss later on.

What makes a trade dependency strategically usable? The Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft has analysed US import dependencies (Sultan and Matthes 2025). Based on this analysis, we derive specific levers for leverage. To do so, we extended the quantitative analysis based on six criteria: the share of US imports Europe supplies; Europe’s global market share (limiting substitution options); control over critical technologies, patents, or production capacity; barriers to US domestic production (capital intensity, lead times, specialised know-how); whether the good is essential for critical sectors (energy, defence, health, digital infrastructure); and whether the global market is already undersupplied. Not every European export strength passes this test.

The semiconductor industry illustrates why. Europe controls the monopolist in EUV lithography machines through ASML—the technology indispensable for manufacturing cutting-edge chips. Yet strategic leverage is limited. ASML sources components from over 5,000 suppliers worldwide, including critical light sources from its US subsidiary Cymer; parts are, in the words of ASML’s CFO, “shipped back and forth between Europe and the US multiple times” (Entropy Capital 2025). When supply chains zigzag across geopolitical blocs, unilateral export controls backfire on the controlling party. The Nexperia case has demonstrated this vividly: after the Dutch government took control of the Chinese-owned chipmaker in October 2025, Beijing responded within days with export restrictions (Hazarika 2025). VW, Nissan, and Honda reported production shortfalls; Honda temporarily halted North American manufacturing, projecting losses of 110,000 vehicles (Meredith 2025). Intervention in one part of the value chain immediately had an impact on Europe’s industry.

Where Europe does have asymmetric leverage is in products with concentrated European supply chains that do not zigzag between geographies. Two stand out: low-enriched uranium (LEU) and gas turbines. Specialised blood products also have the right value chain properties but do not seem suitable on ethical grounds.

Low-enriched uranium (LEU): The Trump administration’s nuclear ambitions are enormous: executive orders signed in May 2025 target a quadrupling of US nuclear capacity to 400 GW by 2050, with ten large reactors under construction by 2030 and three pilot reactors reaching criticality by July 2026 (Martucci 2025b). The US will not be able to provide enough fuel domestically in the short to medium term. The US has limited domestic enrichment capacity, and Russia has historically been the largest provider of such services (U.S. Energy Information Administration 2025). Congress passed a limited ban on LEU imports from Russia in 2024, allowing waivers until 2028 in case of insufficient alternative supplies. The ban is set to expire in 2040 (H.r.1042 – Prohibiting Russian Uranium Imports Act 2024). Yet enforcement appears weak: latest trade data suggests imports from Russia continue largely unchanged[1]. Experts observe that “[b]usiness is operating in a way that is convenient and familiar, receiving government endorsements despite the often harsh rhetoric from officials” (Gorchakov 2025). All of this suggests that sourcing sufficient LEU for US reactors is likely to be a challenge.

Going forward, the US will have to rely heavily on European suppliers. They already provide approximately 80 percent of US LEU imports today—a share that continues to rise (U.S. International Trade Commission 2026). The two most important suppliers are the Dutch, British, and German consortium Urenco and France’s Orano. Both companies also possess the knowhow and the patents for the critical centrifugal technology. If Europe decided to prioritise its own supply by restricting exports to the US, this would not cause immediate supply disruptions. Fuel rod replacements occur every 18 to 24 months and stockpiles exist. But they would directly jeopardise the administration’s nuclear scaling ambitions.

Europe’s leverage here lies in amplifying uncertainty within an already fragile environment. Scaling a capex-heavy industry like nuclear is an enormous coordination challenge even without external friction. Governments and companies must align amid shifting political and commercial winds. Supply chains must scale in lockstep so that every firm receives its inputs and can recover its investment. And investment horizons stretch decades, demanding a stable market environment. The US government will have to do everything it can to provide that stability, predictability, and coordination—an unreliable fuel supplier would directly undermine the effort. LEU may thus be relevant not only for generating leverage but also as a reminder of why reliable cooperation matters. In this capacity, it may serve a preventive function when relationships threaten to turn confrontational.

Gas turbines: The AI-driven data centre boom has created acute demand for power generation. US utilities and hyperscalers plan roughly 250 GW of new capacity by 2030, with data centres accounting for 20 to 30 percent of incremental demand. Grid expansion cannot keep pace with this. Thus, data centres require “behind-themeter” on-site generation; GE Vernova reports that operators expect 30 percent of facilities to rely on dedicated power by 2030. Much of it is likely to be gas for which one needs turbines (Besner 2025). The global gas turbine market is dominated by three manufacturers—GE Vernova (US), Siemens Energy (Germany), and Mitsubishi Power (Japan)—who together supply two-thirds of turbines under construction (Martos 2024). The market is chronically undersupplied: GE Vernova’s backlog reaches 80 GW extending to 2029; lead times have stretched from 2.5–3 years to as much as seven years (Martucci 2025a; Anderson 2025). In the strategically critical 40-60 MW segment for data centre onsite generation, Siemens Energy dominates the market with its SGT-800 series and crucially, with 12–36 month delivery times rather than seven years. Unlike semiconductors, the supply chain for building the SGT-800 is concentrated in Europe: development and manufacturing happen in Finspång (Sweden), with critical components coming from UK-based Materials Solutions (ITEA, n.d.; POWER Magazine 2016).

Export controls or European customer prioritisation for these medium-sized turbines would create asymmetric pain in the short term: If European orders are simply prioritised over US ones, there would be no commercial short-term loss for Europe. For the US, we estimate that a delay of data centre projects could cost as much as EUR 50 billion for US hyperscalers. If, in the worst case, spare capacity planned for US orders cannot be used for European orders, the maximum revenue impact for Siemens Energy would be EUR 7 billion. This is a lot for an individual company but very little for Europe as a continent. If additional measures are required, one could go even further than restricting the export of 40 to 60 MW turbines: GE Vernova itself depends on European production sites in Belfort and Bourogne (France) and Hungary for critical turbine components (GE Vernova 2026).

Two key regulatory elements are missing to turn turbines into effective leverage: First, even if the impact is asymmetric, a EUR 7 billion shock is a big problem. A compensation mechanism for such a shock therefore seems important, not least to make the possibility of ACI activation credible. This applies at both the corporate and the country level. If a company takes a hit of EUR 7 billion to protect Europe, the costs should be spread across the continent. This also seems essential to make ACI activation a plausible option from a political economy perspective. Second, Europe currently cannot simply prioritise European orders unless a supply-crisis state has been declared. The newly adopted European Defence Industry Programme (EDIP) does allow priority-rated orders during declared supply crises—but only once a crisis is declared and the product is crisis-relevant (Regulation (EU) 2025/2643 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 December 2025 Establishing the European Defence Industry Programme and a Framework of Measures to Ensure the Timely Availability and Supply of Defence Products 2025, Art. 60, 63). The US Defence Production Act on the other hand explicitly authorises the use of priority orders for projects that maximise domestic energy supplies (PART 700—Defense Priorities and Allocations System 2025, § 700.20).

While the short-term costs of export restrictions on turbines seem manageable, the medium- to long-term consequences may be more problematic. They are likely to further accelerate investment into production capacity in the US. Siemens Energy has already committed to investing one billion US dollars in American grids and turbine manufacturing (Betz and Colton 2026). This is a sizeable commitment considering Siemens Energy’s total capital expenditures amounted to EUR 1.7 billion for 2025 (Siemens Energy AG 2025b). The loss of manufacturing capacity in Europe weakens both its future leverage and its economy.

There are two possible responses to this: First, Europe needs to work hard to remain an attractive location for production. Focusing on cost optimisation alone will not achieve this: costs associated with transport and currency hedging already make European-made turbines more expensive, not even mentioning labour and energy costs. Europe has to compete on a different dimension: innovation. Turbines, like many other industrial goods, are complex products. Europe has to be the place pushing the frontier on efficiency and excellence. Second, Europe should focus on effective cooperation with companies. Just as governments need companies, companies rely on government to succeed—especially in sectors like energy. The Siemens Energy annual report underscores this, mentioning the possibility of “public and government funding support” through the EU’s Clean Industrial Deal State Aid Framework (CISAF) or the EU budget (Siemens

Energy AG 2025a). For this support not to be wasted, government should ensure that companies commit to Europe. Footloose capitalism combined with national and regional economic policy is bound to fail.

Blood products. Europe—particularly Germany, Switzerland, France, and Belgium—exports substantial volumes of specialised immunological products, monoclonal antibodies, and antisera to the US. For specific therapies in oncology and rare diseases, the US depends on European suppliers with 6–18 month substitution timelines. However, instrumentalising health products is ethically fraught, domestically difficult to justify, and may trigger immediate US retaliation against European pharmaceutical imports.

The EU’s problem is not a lack of leverage in supply chains—it is the difficulty of deploying that leverage as a union of nation-states. Using product leverage requires political decisions that create winners and losers: some countries bear the costs of trade measures while others benefit from ending a third party’s coercive action. Yet no single European institution can make such decisions; the EU prefers rule-based governance over sovereign discretion.

The ACI marks an important step, because it actually enables the delegation of power: member states have agreed to empower the Commission—under certain conditions—to take decisions that may significantly harm their own commercial interests. But legal authority does not guarantee political will. The effectiveness of any deterrent depends on adversaries believing it will actually be used. The Greenland episode has revealed how views diverge. French President Macron explicitly called for ACI activation; German Chancellor Merz refrained (dpa 2026). Germany’s greater trade dependence explains its caution: it stands to lose more from escalation. In the absence of a unified European decision maker Max Krahé calls for “transparent horse trading” (Krahé 2024): pre-negotiated packages where every member state gains something and loses something. The task ahead is to assemble such packages for strategic goods before a crisis hits, so that countries bearing the costs of ACI activation know in advance how they will be compensated.

One might object that such coordination is unnecessary—after all, Germany was overruled on EV tariffs against China. But there is a crucial distinction between reacting to imports that some view as problematic and proactively selecting products for retribution. The latter requires actively choosing to impose costs on a trading partner—a far harder decision for any political union than warding off an external threat. Yet given the current geopolitical environment, it is a problem worth solving.

3.3. Financial leverage: When safe havens aren’t so safe

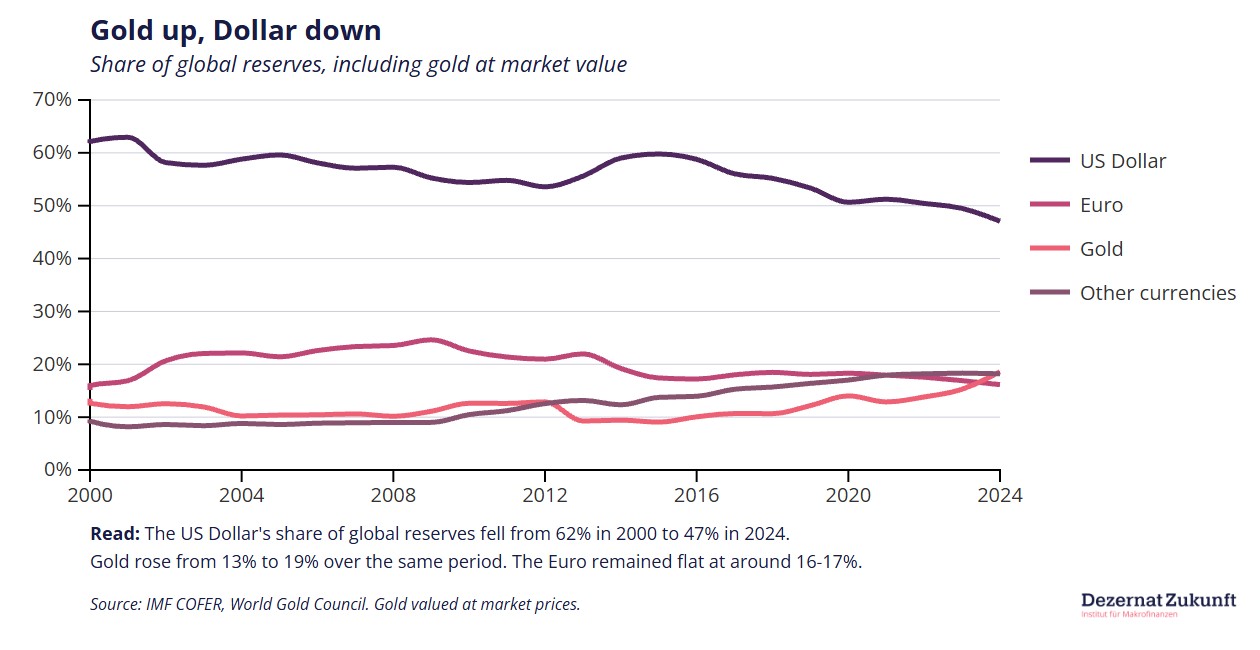

At first glance, the US commands unparalleled financial power. The US dollar remains the world’s dominant reserve currency, accounting for roughly 58% of global foreign exchange reserves despite a gradual decline over the past two decades (Gerresheim et al. 2025). US Treasuries (USTs) are the most traded sovereign bonds globally, with USD 30 trillion outstanding—of which European investors hold nearly 10%. In European financial centres, especially London, USTs are the most actively traded bonds, representing over one-third of trading volume in 2024 (ICMA Secondary Market Practices Committee 2024). This financial architecture, one might argue, grants Washington extraordinary power: it can finance massive deficits at comparatively favourable rates, impose sanctions that cut adversaries off from dollar clearing and gets to set the world’s most important interest rate.

One critical source of this power is the Federal Reserve’s network of currency swap lines—bilateral agreements that allow foreign central banks to obtain dollars in exchange for their domestic currency during periods of market stress. These swap lines proved essential during the 2008 financial crisis and again in March 2020, when the Fed rapidly extended or expanded swap lines with fourteen central banks to stabilise global dollar funding markets. For banks and corporations outside the US with dollar-denominated liabilities—a legacy of decades of dollar-based international trade and finance—swap line access can be essential to survival in a crisis. Doubts have emerged about whether the Trump administration would activate swap lines unconditionally in future crises, or weaponise them as a geopolitical tool, given its transactional approach to alliances.

Yet weaponising swap lines may be profoundly selfdefeating. If the Federal Reserve withheld dollar liquidity during a financial panic, foreign banks and asset managers holding USTs would be forced into fire sales—dumping Treasuries to obtain the dollars they desperately need. This would drive UST yields sharply higher, immediately increasing US government borrowing costs and tightening financial conditions across the US economy. The “nuclear option” of swap line denial would thus inflict acute pain on the US itself. This reveals a deeper truth: US leverage is constrained not just by countermeasures, but by global capitalism. The dollar’s role as the global reserve currency creates dependencies—but those dependencies run in both directions.

The US has less unilateral leverage than assumed not only in crises. The everyday functioning of the UST market reveals deeper vulnerabilities. Several severe stress episodes have recently rocked the market. In March 2020, as COVID-19 spread, the “safe haven” asset experienced a violent sell-off; yields spiked and liquidity evaporated until the Federal Reserve intervened with USD 1.1 trillion in bond purchases (U.S. Government Accountability Office 2021). A similar, though less severe, episode occurred in early 2025 when yields on 30-year Treasuries briefly breached 5%—a psychologically critical threshold that reportedly prompted Trump to announce his 90-day tariff pause (Dryden 2025). These disruptions follow a common pattern: rapid yield movements trigger automatic selling by leveraged investors, particularly hedge funds, amplifying price swings in a destabilising feedback loop (International Monetary Fund 2025a).

The composition of UST demand has shifted fundamentally in ways that erode stability. Economists Paul Krugman and Brad Setser argue that the dollar’s traditional “safe haven” status is deteriorating; investors now buy Treasuries primarily for yield rather than safety

(Krugman 2025; Setser 2025). Foreign central banks—historically stabilising buyers accumulating reserves—have stopped buying; private investors, especially hedge funds have become dominant net buyers. Hedge funds do not hold USTs for their safehaven status but because they can currently profit from highly leveraged trades arbitraging between actual USTs and futures contracts. Once that is no longer the case, they may disappear as quickly as they came.

The UST market is far from being one with captive buyers insensitive to information, as one would expect from a safe asset (Gorton 2016). Instead, UST yields have become highly sensitive to political decisions. Reuters even described the current state as a “fragile peace” between the Trump administration and bond markets, noting how carefully officials calibrate messaging to avoid spooking investors (Reuters 2025). Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent explicitly acknowledged this dynamic, calling himself “the nation’s most important bond salesman” and stating that yields are “an important barometer” of his success.

This fragility matters for both government finances and the broader economy. The US must finance a deficit of USD 1.8 trillion—5.9 percent of GDP—through bond issuance (Congressional Budget Office 2025). Every 20 basis point increase in yields costs the federal government over USD 60 billion annually. But the damage extends beyond Washington’s budget: UST yields serve as the benchmark for all other dollar credit. When Treasury yields rise, borrowing costs across the economy follow, slowing growth and squeezing households. Trump has taken note, instructing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—the governmentsponsored entities that securitise mortgages—to buy USD 200 billion in mortgage bonds (Breuninger and Melloy 2026).

Whether Trump’s nominee for Fed chair, Kevin Warsh, changes this is doubtful: Krugman calls him “a political animal” whose views track power rather than data (Krugman 2026), and markets priced in cuts on his nomination (Brooks 2026a, 2026b). The administration is also pursuing “cryptomercantilism”—promoting dollardenominated stablecoins backed by USTs (van ’t Klooster et al. 2025)—but the attempt itself signals anxiety about eroding demand from traditional sources.

Given these developments, Europe has more financial leverage than commonly assumed. Three levers stand out:

Regulatory reform: European sovereign bonds are currently not treated as a preferred asset class in European and British banking regulation. Under the leverage ratio, they count as equally risky as foreign-currency sovereign bonds, including USTs. The leverage ratio requires ECB-supervised banks to hold high-quality capital equal to 3 percent of total assets—including sovereign bonds (European Central Bank 2024). This is meant to make banks safer but also limits their capacity to hold sovereigns and increases costs (Bräuning et al. 2025), making sovereign holdings unattractive for banks and constraining their willingness to deploy scarce capital. The ratio of sovereign bonds to capital on bank balance sheets currently stands at 80 percent of its historical maximum (Ampudia et al. 2025). Hedge funds and foreign banks are increasingly taking over the warehousing function for sovereign bonds. Bessent is therefore pursuing reform of the supplementary leverage ratio to exempt USTs (Bessent 2025). Europe, by contrast, plans to continue treating all sovereign bonds equally. This makes no sense. European sovereign bonds could also be exempted from the leverage ratio—they are always safer in the Eurosystem than dollar bonds, since the ECB can act as lender of last resort if needed (the same applies to Gilts in the UK). The side effect: USTs would become much less attractive compared to European bonds.

Similarly, Europe, and the UK in particular, could introduce higher margin requirements on repo transactions—the short-term borrowing that hedge funds use to amplify returns (as is already under discussion for the Gilt market, see (Bank of England 2025)). Hedge funds are now among the largest UST holders; making this funding more expensive would dampen their demand while improving financial stability—a measure justifiable entirely on prudential grounds. One may worry that this also affects hedge fund holdings of European government bonds. But if banking regulation allows banks to hold European sovereign bonds at little or minimal cost, there would be no need for them to be warehoused by hedge funds in the first place. Thus, the two regulatory changes could be particularly fruitful in combination. First, banking rules that shift European sovereign bonds back onto bank balance sheets. Second, hedge fund regulation that makes highly speculative trades with the remaining government bond less profitable. Needless to say, the effectiveness of such regulatory changes would depend heavily on collaboration between the EU and the UK, given London’s outsized role as the world’s financial centre.

Tax-based differentiation: Europe may want to go beyond regulation, however, considering its investment needs and the substantial outflows of capital to the US in recent years. According to the Draghi report an additional EUR 750–800 billion is required to make Europe competitive again (Draghi 2024). One way to incentivise investment in Europe could be to introduce a levy on European purchases of US assets. The US imposed such a levy between 1964 and 1974, the Interest Equalization Tax. The tax, designed to stem capital outflows, added roughly one percentage point to the cost of foreign investments by taxing US purchases of foreign securities at rates between 2.75 percent and 15 percent depending on maturity (Pomp 1974; United States Congress, Joint Committee on Internal Revenue Taxation, United States Dept. of the Treasury and United States Congress Senate Committee on Finance 1964). It successfully reduced outflows but also spurred the development of the Eurodollar market in London as investors circumvented New York. The historical precedent demonstrates effectiveness but also reiterates the critical importance of UK participation: without London, capital simply relocates. Coordinating such a measure between the EU and UK would be essential, which points to a broader strategic need to deepen financial cooperation despite Brexit.

Europe’s biggest oversight in the area of financial leverage may be its failure to capitalise on the dollar’s declining reserve status. While the dollar’s share of global reserves has fallen from 62 percent to 47 percent over two decades (Gerresheim et al. 2025), the euro has not captured this outflow—gold and other currencies have. This represents a profound missed opportunity. As confidence in the dollar wavers, there is no credible alternative. European financial centres—especially London—are critical nodes in UST trading infrastructure; European banks and asset managers hold substantial Treasury positions; and the euro remains the world’s second reserve currency, at least in theory. Yet the euro is failing spectacularly to fill the void left by the dollar.

This could be addressed in a targeted way:

European Reserve Asset: The euro’s role as a reserve currency is hampered by the lack of safe assets. The ECB’s 2005 decision to base bond eligibility on private credit ratings—rather than treating all eurozone sovereign debt as equally safe—fragmented the market (Schuster 2023). Given the political disagreements around the treatment of European sovereign debt, a realistic near-term path may be for the European Central Bank to introduce a European Reserve Asset, a euro-denominated instrument sold to foreign central banks with flexible maturities, functioning essentially as a deposit facility at the ECB. One may ask why Europe’s governments would not want to take advantage of lower borrowing costs, especially given current borrowing needs for defence, by issuing the safe asset themselves. Yet if they cannot agree—which seems unlikely—a safe asset issued by the ECB seems like the next best solution, at least for establishing a reserve currency.

Liquidity lines: The ECB could make this European Reserve Asset even more attractive by extending liquidity lines to non-European central banks that maintain significant euro reserves. Such lines come in two forms: swap lines, where central banks exchange currencies directly and repo lines, where the ECB lends euros against euro-denominated collateral. Repo lines matter most for countries seeking euro liquidity without reciprocal arrangements. The ECB is already moving in this direction. In February 2026, President Lagarde announced that the ECB is “reframing” its repo lines to make them “more attractive to other national central banks outside the euro area and outside Europe” (European Central Bank 2026). Expanding these facilities is a concrete step toward establishing the euro as a credible reserve alternative.

None of these measures will transform global financial markets. But in a fragile market where Trump watches yields obsessively and a 20-basispoint move costs USD 60 billion, marginal shifts matter. Strengthening the euro’s international role has become a common talking point that not every policymaker seems to take seriously (and there are reasons why a stronger euro may not be desirable; see (Gerresheim et al. 2025)). Yet the global financial system struggles without a safehaven currency (Eichengreen 1996), and China is reasserting its yuan ambitions (Bloomberg News 2026). Europe should look past the sheer size of the Treasury market and engage in financial statecraft.

3.4. Digital leverage: A stable but asymmetric equilibrium

Digital infrastructure illustrates how raw power fails to translate into usable leverage. The US dominates every layer: deep-sea cables, internet exchange points, satellite networks, data centres, cloud services, operating systems, semiconductors and frontier AI models. Yet despite this commanding position, it has not weaponised its digital power against Europe.

This restraint reflects a stable equilibrium built on mutual dependence. US tech companies generate a substantial share of their revenue from Europe and need continued access to justify their valuations. The US also benefits from what Farrell and Newman call the panopticon effect: passive intelligence access through global infrastructure (Farrell and Newman 2019). Weaponising infrastructure would jeopardise both commerical revenue and state surveillance capabilities. The US has weaponised its digital leverage in the case of Russia 2022 and Huawei, but both cases are not comparable given their minute commercial relevance compared to Europe. The EU needs US digital infrastructure, and the US has no interest in leveraging its own digital infrastructure for political and commercial reasons. The political equilibrium looks rather stable with neither player using the digital sphere to force policy choices or actions on the other one.

But within this equilibrium, both players exercise power. US law propagates through commercial dependencies into European firms and institutions. This constrains and shapes the behaviour of individual actors and companies in Europe. The 2025 ICC case—where US sanctions disrupted the chief prosecutor’s Microsoft email—demonstrated that American infrastructure extends into European institutions (Sayers 2025). What is notable, though, is how the US seeks to avoid leaving the equilibrium.

As such, the CLOUD Act, passed in 2018, which US authorities can use to force US providers to disclose data regardless of its storage location (in conflict with the GDPR) seems hardly used.

Europe, for its part, regulates and fines. Of the close to EUR 7 billion in fines imposed for GDPR violations, US companies had to pay EUR 4 billion (CMS Law 2026). The Digital Markets Act designates six American companies as “gatekeepers” subject to fines up to 10 percent of global turnover and, in theory, structural remedies including divestiture. In practice fines have remained far from that, with Apple being charged EUR 500 million for unfair App Store practices and Meta EUR 200 million for its pay or consent model under which users either had to consent to their data being used for targeted ads or pay (Hobbelen and Wouters 2025). These instances of European regulation represent a tax on market access, not leverage over US policy. Equally, no major US tech firm has exited Europe; no US policy has changed in response to European regulation.

Just because the US does not actively use digital to exert leverage does not mean Europe is in a comfortable position. Each new AWS contract is another compliance surface. Power scales with adoption. What can Europe do? In the short term, wrapping US technology in European legal structures such as the sovereign cloud initiatives—S3NS (Thales–Google), Bleu (Orange–Capgemini–Microsoft), Delos (SAP–Microsoft)—might be the best option. But such initiatives don’t change the fundamentals. In the long term, Europe needs to aim higher. Not for complete digital sovereignty or replacement of US infrastructure. The goal has to be what Teer et al. call becoming “strategically indispensable” in the digital value chain (Teer et al. 2024)—building capabilities that create mutual rather than one-way dependence.

This requires European companies that can compete at scale. To grow those, Europe needs to tackle several challenges from the commercialisation of foundational research to large-scale funding and government contracts. It needs to focus on regaining a competitive edge in innovation and becoming much better at spreading new technologies. Even though this may sound like an industrial policy project, it is not. It is a project that will only succeed if everyone from the preschooler to the experienced investor can contribute, ensuring technologies diffuse, use cases are developed and perfected. In sum, yes, the equilibrium protects Europe from the worst outcomes. But equilibria can shift—and the conditions for US leverage are building while Europe’s countervailing position erodes.

3.5. Energy leverage: From one dependency to another?

Few topics preoccupy European policymakers more than energy dependency. Headlines warn of a US “stranglehold” on European gas supply (The Guardian 2026); German Chancellor Merz has been travelling to Qatar in an effort to reduce dependency on the US.

Europe’s pivot away from Russian gas has created a new structural dependency on American LNG driven by the confluence of three forces. First, natural gas remains an essential pillar of Europe’s energy system during the transition. It still provides around a third of EU-wide heat generation and is central to securing power system flexibility as other dispatchable fossil generation is phased out and the share of intermittent renewables is rising. Second, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine forced a rapid exit from Russian pipeline gas, creating an immediate supply gap that could not be offset by gas demand reductions alone. Third, a massive US LNG export push, driven by plentiful and cheap US gas, can now be absorbed by increased European regasification capacity.

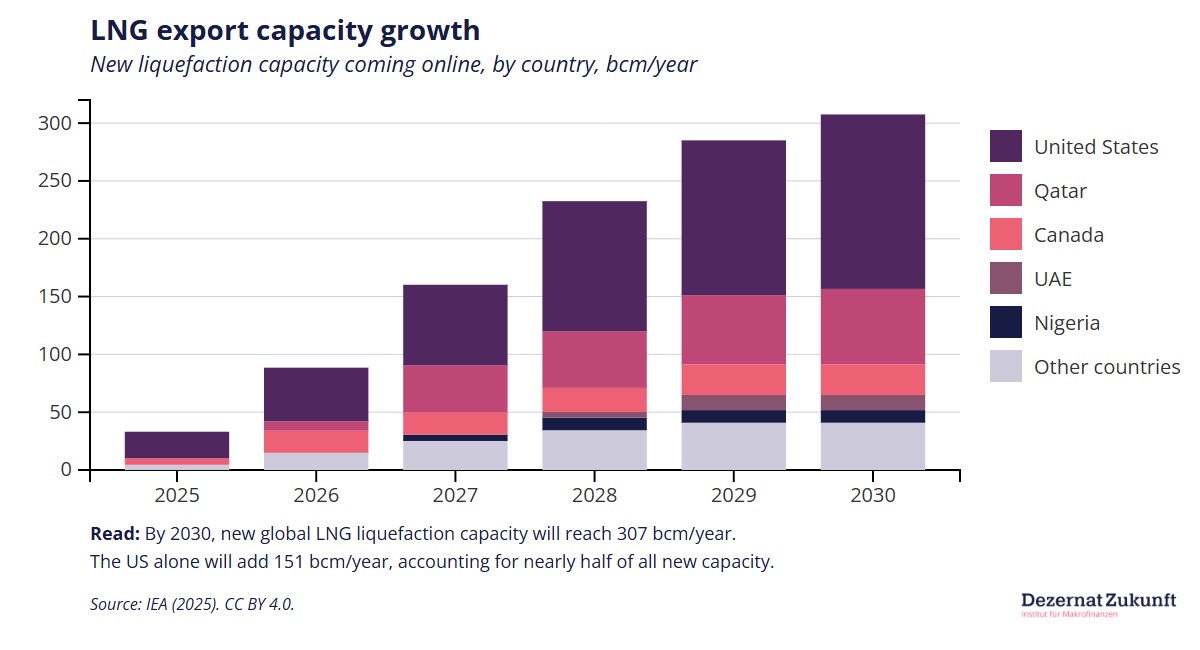

Between 2021 and 2025, European gas consumption declined by 19 percent, yet LNG imports surged as pipeline supplies collapsed (Keliauskaite˙ et al. 2025). US LNG imports increased fourfold since 2021, and the American share of Europe’s total LNG imports more than doubled, rising to 58 percent (Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis 2025). As Europe prepares to end all gas imports from Russia by the end of 2027 (Council of the European Union 2026), US LNG is likely to play an even bigger role in the future. This reflects not only Europe’s need for increased LNG imports, but also the massive expansion of US liquefaction capacity, increasing by around 150 bcm until 2030 (International Energy Agency 2025a). For comparison, current global liquefaction capacity amounts to 670 bcm (International Energy Agency 2025c). Plentiful American LNG will meet European demand. Europe’s increasing reliance on US LNG thus seems like a path of least resistance.

Such dependency carries significant systemic risk, however, as Europe learned after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The doubling of gas prices in 2022 (TTF, compared to the average of 2019-2021), and the fear of gas shortages triggered intense societal debates and major government action, such as the EUR 200 billion fiscal shield announced by the German government in the summer of 2022. But the associated price spikes have an even greater impact on the economy through a systemic accelerant: merit-order pricing in European electricity markets. Under this system, the most expensive generating unit needed to meet marginal demand sets the clearing price paid to all producers (Hirth 2022). While efficient, this system gives gas-fired power plants an outsized role. They set the electricity price about 40 percent of the time (Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators 2024). Gas prices thus drive energy prices more broadly, which are in turn the most important driver of inflation in Europe. Every rate-hike cycle since European central banks began targeting inflation has been triggered by rising energy prices (Sigl-Glöckner 2024). Research by the European Central Bank on the 2022–2023 energy crisis finds that a ten percent increase in gas prices raises inflation by roughly 0.1 percentage points (López et al. 2024). Gas dependency is thus an inflation vulnerability, with direct implications for monetary policy, real wages, and political stability.

This vulnerability is most acute at present. According to the IEA, global LNG market fundamentals “remained tight” through the first half of 2025 (International Energy Agency 2025b). Relief will arrive only from mid-2026, when Qatar’s North Field East expansion and major US projects come online, triggering supply growth of 7 percent—the strongest since 2019. Until then, Europe faces a window of heightened exposure. The German government’s urgent diplomacy in the Gulf reflects this reality.

From 2027 onward, three market developments will constrain US ability to weaponise this dependency.

Surplus capacity: In its latest gas outlook, the IEA projects an LNG surplus of 65 bcm by 2030—more than 20 percent of the supply to be added between 2024 and 2030 (International Energy Agency 2025a). If these projections hold, sellers will be pressed to find buyers, not the other way around. Also, around 220 bcm of active LNG contracts are set to expire by 2030, less than 5 percent thereof sold from the US. For Europe, these expiring contract volumes create new contracting opportunities.

Increasing liquidity and flexibility: The LNG market has become increasingly liquid and flexible over recent years. This trend is set to continue: The share of uncontracted LNG in total global LNG supply is expected to increase from around 25 percent to 35 percent between 2026 and 2030 (Bloomberg New Energy Finance 2025). At the same time, contracts have become more flexible. According to the IEA, the share of destination-free LNG contracts increased from 29 percent in 2016 to around 45 percent in 2024 (International Energy Agency 2025a). Flexibility is further enhanced by the rise of portfolio players; their share of procurement contracts among all LNG contracts in force rose from 26 percent in 2016 to more than 38 percent in 2024, reflecting the growing importance of portfolio optimisation and crossregional arbitrage. This share is projected to increase further, reaching close to 44 percent by 2030 (International Energy Agency 2025a). In sum, the LNG market is becoming more oil-like in terms of liquidity and flexibility – reducing suppliers’ ability to weaponise dependencies without self-harm.

Europe as the only profitable destination: Europe is the most attractive destination for US LNG. Short shipping distances from the US Gulf Coast and Europe’s high willingness to pay for flexible cargoes mean that European sales often set the upper bound for US netbacks (destination price minus costs associated with selling to abroad). Restricting exports to Europe would shift marginal cargoes towards Asia, putting additional downward pressure on Asian spot prices in the medium term, which are already set to converge with long-run marginal US export costs by 2030 against the background of the global supply glut (Bloomberg New Energy Finance 2025). While these price reductions are expected to stimulate additional gas demand from oil-to-gas switching, which becomes economic at around EUR 23/MWh across Asian markets, Asian spot prices may even fall towards US short-run marginal costs at around EUR 17 to 20/MWh. Add longer voyage distances to Asia, which increase freight costs, and the margin compression intensifies. The result: exporter profits could fall toward zero or even turn negative. Lower and more volatile netbacks would create domestic political backlash within the US. The kill switch exists in theory, but pulling it would severely damage America’s LNG export industry.

Yet even with favourable market conditions, Europe remains exposed to US political risk through the permitting process. Under the Natural Gas Act, the Department of Energy must determine that LNG exports to non-FTA countries—which includes Europe—are in the “public interest” (Ratner 2026). The Biden administration’s 2024 pause on new export authorisations demonstrated how this mechanism can bite without warning. While existing authorisations and contracts remain protected, future capacity expansion depends on regulatory approval that can shift with each administration.

Even without deliberate weaponisation, LNG dependency exposes Europe to structural price volatility. Political volatility—Trump’s transactional approach, shifting regulatory postures and unpredictable trade linkages—compounds market volatility. Europe cannot count on favourable LNG market fundamentals to protect it when the political environment remains so uncertain.

Worse, restricting LNG exports could serve the US government’s domestic interests: Surging electricity demand from data centres is pushing US gas and power prices higher, putting upward pressure on inflation; restricting LNG exports could bring them down. Trump may not be held back by commercial considerations—he may be encouraged by them. Europe needs to act. Three pathways offer protection:

Diversification: The global LNG market is entering a phase of structural oversupply from 2027. This creates opportunities: in the medium term, largely replacing US LNG seems possible. In a bullish US scenario, in which Europe actually buys energy imports from the US to the tune of USD 750 billion as agreed in the trade deal and gas demand reductions falter, LNG imports from the US could reach 115 bcm by 2030 (Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis 2025). This would represent the upper limit of LNG imports from the US. Uncontracted non-US volumes in 2030 far exceed this, amounting to up to 165 bcm (Bloomberg New Energy Finance 2025). Also, around 220 bcm of active LNG contracts are set to expire by 2030, less than 5 percent of which are from the US (International Energy Agency 2025a). To unlock this diversification potential, Europe should actively reduce dependence on US LNG through public-led diversification. This could include directing state-owned buyers to limit US purchases, transforming the EU’s joint gas purchase mechanism, AggregateEU, into a strategic diversification tool that excludes not only Russian but also US supplies, or introducing a quota that applies duties to excess US LNG imports.

Structural demand reduction: Reducing gas consumption would ease the transition away from US LNG and reduce exposure to price volatility. Energy system studies suggest that structural measures–expansion of renewables and storage, efficiency measures and electrification–could reduce EU gas demand by up to 27 percent by 2030 across the power, buildings and industry sectors (Graf et al. 2023; Matthes et al. 2023). This would equate to 86 percent of 2025 US LNG imports to Europe. Each billion cubic metres saved directly reduces dependence on US LNG and helps to gradually reduce the gas-price passthrough and wider inflation impacts. Europe should thus double down on structural gas reduction efforts.

Gas reserve: A larger gas reserve would cushion the short-term impact of an abrupt US LNG disruption, giving Europe more time to reroute flexible cargoes—reducing both the risk of a supply gap and the intensity of price spikes. Europe should therefore fully utilise its storage potential, including spare capacity in Ukraine, which has the largest underground storage in Europe (Hoisch 2025). Ukraine’s spare capacity alone would cover three months of US LNG imports. A European strategic gas reserve that is open for Ukraine participation could unlock this potential.

Beyond the short term—where considerable friction would emerge from a US LNG disruption—the challenge may prove less daunting than headlines suggest. A large, liquid market is inherently difficult to control. Yet the US wields power beyond market fundamentals: it can shape the entire LNG market through secondary sanctions, as the fate of Russia’s Arctic LNG 2 project demonstrates. When commercial leverage, permitting authority, and sanctions power converge, prudent actors reduce their exposure. Europe should use the coming supply glut to diversify away from US LNG—not to settle into a new comfort zone.

4. Concluding thoughts

The US is undoubtedly a superpower—unlike

Europe (even taken as a whole). By any raw measure of chips—economic, military or technological—the US alone holds far more than Europe’s ten largest economies taken together. Yet as this paper has shown, raw power is not the same as leverage.

Europe has more leverage than it thinks:

Across the dimensions examined, Europe holds meaningful cards. Europe is a key trading hub for US Treasuries. Regulatory changes could shift demand away from dollar assets toward eurodenominated bonds. Europe controls chokepoints in low-enriched uranium, supplying 80 percent of US imports, and in gas turbines, where Siemens Energy’s medium-sized models dominate a chronically undersupplied market. With regards to energy, the coming LNG supply glut will transform the market into a buyer’s market where Europe—as the most profitable destination for US exporters—holds the upper hand. Finally, Europe’s USD 10 trillion consumer market is indispensable: US technology companies cannot justify their valuations without access to 450 million wealthy European consumers.

The US position is more fragile than it appears: As much as the US dominates global markets, it also depends on them. Demand for US Treasuries depends on hedge funds in London; the value of American pension savings depends on the Magnificent Seven—Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Alphabet, Nvidia, Tesla, and Meta—being able to sell to the world’s second-largest consumer market; and US investments in LNG export capacity depend on Europe as a buyer.

European leverage is not a reason for complacency—it is a reason for confidence: Europe does not need to fear American power if it understands its own position. The mutual dependencies documented in this paper mean that Europe has space to act: to shape its own future, to build its own capabilities, and to defend its interests without succumbing to coercion. Leverage provides the strategic breathing room to make long-term investments in European strength rather than shortterm accommodations to American pressure.

To capitalise on this position, Europe should act on five fronts:

- Make the Anti-Coercion Instrument credible: The ACI provides the legal framework for product leverage, but legal authority does not guarantee political will. Europe needs prenegotiated package deals that specify how costs will be distributed when the instrument is activated. Transparent horse trading before a crisis is the only way to make the threat credible. Without such arrangements, member states bearing the costs of trade measures will block activation—and adversaries know it.

- Enable priority procurement in the energy sector: The US Defence Production Act explicitly authorises priority orders for inputs that maximise domestic energy supplies. Europe has no equivalent. The European Defence Industry Programme allows priority-rated orders only during declared supply crises. Europe should match American capabilities: the ability to prioritise European orders for strategic goods like gas turbines before a crisis is declared, not after.

- Strengthen Europe’s digital position: In the short term, this means wrapping US technology in European legal structures—sovereign cloud initiatives that ring-fence data and compliance to a certain extent. In the long term, Europe must build companies that can compete at scale in the digital value chain. The goal is not autarky but strategic indispensability: capabilities that create mutual rather than one-way dependence.

- Treat the design of financial markets as a geopolitical issue: Specifically this means reviewing regulation that treats European sovereign bonds no differently than US Treasuries, considering whether capital outflows to the US are in Europe’s best interest and developing the euro into a serious reserve currency. This will require an ample supply of reserve assets and be aided by the reliable presence of liquidity lines. The dollar will not disappear as a reserve currency from one day to the next but in a fragile Treasury market marginal shifts matter. Equally, re-evaluating the status of US Treasuries and the dollar seems the only responsible thing to do given recent developments. A reserve currency requires a stable and reliable political system in the background.

- Build political capacity for intergovernmental action—including the UK: The European Commission’s structures are designed for rule-based governance, not sovereign discretion. Yet exercising leverage requires rapid political decisions that create winners and losers. Thus, Europe needs to strengthen intergovernmental action on strategic questions—decoupled from consensus requirements and technocratic caution. Otherwise it will struggle to convert material chips into effective leverage. Given the UK’s role in financial markets and the size of its economy, it is central to these efforts and should be included regardless of whether it is part of the EU or not.

Actively choosing one’s destiny should be a priority after what Gloger and Mascolo pointedly call “the failure”: Germany’s past policy towards Russia (Gloger and Mascolo 2025). Germany allowed itself to become structurally dependent on a country that was not even large by economic measures. Russia’s GDP never exceeded USD 2.3 trillion—smaller than Italy’s (World Bank 2024)—yet it managed to capture 40 percent of Europe’s gas imports by 2021 (International Energy Agency 2022), creating leverage far out of proportion to its material power. If Europe (including the UK) learns to play its cards smartly and actively works on improving its long-term position rather than getting bogged down in internal politics, it has more leverage than it thinks—enough to defend its position without succumbing to coercion, and enough to remain a consequential actor in a world of intensifying great power competition.

References

- Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators. 2024. Progress of EU Electricity Wholesale Market Integration. Market Monitoring Report. Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER).

- Ampudia, Miguel, Eduard Betz, Anne Duquerroy, Benjamin Hartung, Vagia Iskaki, and Olivier Vergote. 2025. “Constraints on Intermediary Banks Can Undermine Functioning Government Bond Markets.” European Central Bank, September 22.

- Anderson, Jared. 2025. “US Gas-Fired Turbine Wait Times as Much as Seven Years; Costs up Sharply.” S&P Global Energy, May 20.

- Bank of England. 2025. Enhancing the Resilience of the Gilt Repo Market. Discussion Paper. Bank of England.

- Besner, J Andrew. 2025. “Powering the Data Center Boom.” Gas Turbine World, October 17.

- Bessent, Scott. 2025. “Remarks by Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent Before the Treasury Market Conference.” U.S. Department of the Treasury, November 12.

- Betz, Bradford, and Emma Colton. 2026. “Energy Giant Bets Big on US, Says Its Electricity Market ’Hottest’ in the World.” Fox Business, February 3.

- Bloomberg New Energy Finance. 2025. Global Gas and LNG Outlook 2025. Market Outlook. Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

- Bloomberg News. 2026. “China Highlights Xi’s Old Speech on Risks, Powerful Currency.” Yahoo Finance, February 2.

- Bräuning, Falk, Martin Scheicher, and Hillary Stein. 2025. “Dealer Constraints and Government Bond Markets: A Transatlantic Perspective.” SUERF, May.

- Breuninger, Kevin, and John Melloy. 2026. “Trump Says He’s Instructing His ’Representatives’ to Buy $200 Billion in Mortgage Bonds, Claiming It Will Lower Rates.” CNBC, January 8.

- Brooks, Robin J. 2026a. “Five Charts to Track the Warsh Sentiment Shift: Friday’s Crash in Gold and Silver Made Many Think Warsh Is Hawkish – He Won’t Be.” Substack, February 2.

- Brooks, Robin J. 2026b. “What Kevin Warsh Means for Markets: The Dollar Rose Almost One Percent Yesterday, but Not Much of That Was about Warsh.” Substack, January 31.

- Capul, Jason. 2025. “Diversification Illusion? Apollo Flags 401(k) Exposure to Magnificent Seven Group.” Seeking Alpha, October 9.

- CMS Law. 2026. “GDPR Enforcement Tracker.” CMS Law.

- Congressional Budget Office. 2025. Monthly Budget Review FY25. Monthly Budget Review. Congressional Budget Office.

- Council of the European Union. 2026. “Russian Gas Imports: Council Gives Final Greenlight to a Stepwise Ban.” Press Release. European Council, January 26.

- dpa. 2026. “Merz Lässt Die “Handels-Bazooka” Stecken.” Zeit Online, January 19.

- Draghi, Mario. 2024. The Future of European Competitiveness: A Competitiveness Strategy for Europe. Part B: In-depth analysis and recommendations. European Commission.

- Dryden, Alex. 2025. “Jitters in US Bond Market Look Set to Continue.” Yahoo Finance, April.

- Duffy, Clare. 2026. “Trump Administration’s Vision of US Tech Dominance Is Colliding with Europe.” CNN, January 12.

- Eichengreen, Barry. 1996. Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919-1939. Oxford University Press.

- Entropy Capital. 2025. “ASML’s Supply Chain, Bill of Materials, and the Devastating Effects of Potential Tariffs on US Fabs: A Forensic Analysis of the Lithography Monopolists Supply Chain and the Effect of Recent Tariff Policies.” Substack, April 23.

- European Central Bank. 2024. “Leverage Ratio Pillar 2 Requirement (P2R).”

- European Central Bank. 2026. “Monetary Policy Statement Press Conference with Christine Lagarde, President of the ECB and Luis de Guindos, Vice-President of the ECB.” European Central Bank, February 5.

- Eurostat. 2024. “Final Consumption Expenditure of Households.” Eurostat.

- Farrell, Henry, and Abraham L. Newman. 2019. “Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion.” International Security 44 (1): 42–79.

- GE Vernova. 2026. “Europe Region.” GE Vernova, January 13.

- Gehrke, Tobias. 2025. “Brussels Hold’em: European Cards Against Trumpian Coercion.” Policy Brief. European Council on Foreign Relations, March 20.

- Gerresheim, Nils, Max Krahé, and Jens van ’t Klooster. 2025. Die Folgen Einer Euro-Internationalisierung. Dezernat Zukunft.

- Gloger, Katja, and Georg Mascolo. 2025. Das Versagen: Eine Investigative Geschichte Der Deutschen Russlandpolitik. Ullstein Buchverlage.

- Gorchakov, Dmitry. 2025. “Enriched Uranium Fuels Russia’s War Machine. But the US Still Imports It.” Bellona, March 17.

- Gorton, Gary B. 2016. The History and Economics of Safe Assets. NBER Working Paper No. 22210. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Graf, Andreas, Murielle Gagnebin, and Matthias Buck. 2023. “Breaking Free from Fossil Gas: A New Path to a Climate-Neutral Europe.” Study 292/02-S-2023/EN. Agora Energiewende, May 4.

- Hazarika, Rohan. 2025. “Dutch Takeover of Chinese-Owned Nexperia Raises Chip Supply Concerns.” S&P Global Automotive Insights, October 23.

- Hirth, Lion. 2022. “Das Merit Order Model: Preisbildung Auf Strommärkten.” Neon Neue Energieökonomik, September 2.

- Hobbelen, Hein, and David Wouters. 2025. “First-Ever DMA Non-Compliance Fines – Another Step in Big Tech Scrutiny.” Bird & Bird LLP, May 20.

- Hoisch, Matt. 2025. “Naftogaz Proposes EU Strategic Gas Reserves Employing Ukrainian Storage.” S&P Global Energy, October 14.

- H.r.1042 – Prohibiting Russian Uranium Imports Act, Public Law Nos. Pub. L. 118-62 (2024).

- ICMA Secondary Market Practices Committee. 2024. European Secondary Market Data Report H2 2024 – Sovereign Edition. Market Data Report. ICMA Group.

- Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. 2025. “European LNG Tracker.” Interactive Dataset. Institute for Energy Economics; Financial Analysis (IEEFA), October.

- International Energy Agency. 2022. A 10-Point Plan to Reduce the European Union’s Reliance on Russian Natural Gas. Report. International Energy Agency.

- International Energy Agency. 2025a. Gas 2025: Analysis and Forecasts to 2030. Medium-term analysis report. International Energy Agency.

- International Energy Agency. 2025b. Gas Market Report, Q3-2025. Quarterly fuel report. International Energy Agency.

- International Energy Agency. 2025c. “New Data Resource Tracks Global LNG Liquefaction Capacity Additions as Markets Gear up for Record Wave of New Projects.” News Article. International Energy Agency, June 6.

- International Monetary Fund. 2025a. “Chapter 1.” In Global Financial Stability Report. International Monetary Fund.

- International Monetary Fund. 2025b. “World Economic Outlook Database.” International Monetary Fund, October.

- ITEA. n.d. “Siemens Energy AB.” ITEA. Accessed February 4, 2026.

- Keliauskaite˙, Ugne˙, Ben McWilliams, Giovanni Sgaravatti, and Georg Zachmann. 2025. “European Natural Gas Imports.” Dataset. Bruegel.

- Krahé, Max. 2024. “Beyond Maastricht.” Dezernat Zukunft, November 19.

- Krahé, Max, Nils Gerresheim, and Sara Schulte. 2025. “Deal Ja. Gewissheit? Nein.” Dezernat Zukunft, July 29.

- Krugman, Paul. 2025. “We Are No Longer a Serious Country.” June.

- Krugman, Paul. 2026. “A Bad Heir Day at the Fed: No, Kevin Warsh Isn’t Qualified.” Substack, January 30.

- Lima-Strong, Cristiano. 2025. “Europe’s x Fine Is Fueling GOP Angst Toward NATO.” Tech Policy Press, December 10.

- López, Lucía, Florens Odendahl, Susana Párraga Rodríguez, and Edgar Silgado-Gómez. 2024. The Pass-Through to Inflation of Gas Price Shocks. ECB Working Paper No. 2968. European Central Bank.

- Martos, Jenos. 2024. Leading Three Manufacturers Providing Two-Thirds of Turbines for Gas-Fired Power Plants Under Construction. Research Brief. Global Energy Monitor.

- Martucci, Brian. 2025a. “GE Vernova Expects to End 2025 with an 80-GW Gas Turbine Backlog That Stretches into 2029.” Utility Dive, December 11.

- Martucci, Brian. 2025b. “Trump Aims for 400 GW of Nuclear by 2050, 10 Large Reactors Under Construction by 2030.” Utility Dive, May 28.

- Matthes, Felix Christian, Lothar Rausch, and Roman Mendelevitch. 2023. Natural Gas Demand Outlook to 2050. Research Report. Deloitte Sustainability & Climate; Öko-Institut.

- Meredith, Sam. 2025. “Nexperia Crisis: Dutch Chipmaker Issues Urgent Plea to Its China Unit.” CNBC, November 28.

- Meta Platforms Inc. 2025. “Form 10-k Annual Report for the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2024.” U.S. Securities; Exchange Commission, January 30.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2025. “Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on the 2024 National Economic and Social Development.” National Bureau of Statistics of China, February 28.

- OECD. 2024. “Household Savings (Indicator).” OECD.

- PART 700—Defense Priorities and Allocations System, 15.700 Code of Federal Regulations (2025).

- Pomp, Richard. 1974. “The United States Interest Equalization Tax.” Faculty Articles and Papers, no. 572.

- POWER Magazine. 2016. “Historic and Trend-Setting Siemens Turbine Manufacturing Plant Hits Milestone.” POWER Magazine, April 26.

- Ratner, Michael. 2026. Executive Orders and u.s. LNG Exports: Frequently Asked Questions. CRS Report No. R48038. Congressional Research Service.

- Regulation (EU) 2023/2675 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 November 2023 on the Protection of the Union and Its Member States from Economic Coercion by Third Countries, Legis. No. 2023/2675, Official Journal of the European Union (2023).

- Regulation (EU) 2025/2643 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 December 2025 Establishing the European Defence Industry Programme and a Framework of Measures to Ensure the Timely Availability and Supply of Defence Products, Legis. No. 2025/2643, Official Journal of the European Union (2025).

- Reuters. 2025. “The Tenuous Peace Between Trump and the $30 Trillion US Bond Market.” December 29.

- Sayers, Owen. 2025. “Microsoft’s ICC Email Block Reignites European Data Sovereignty Concerns.” Computer Weekly, May 23.

- Schuster, Florian. 2023. Sovereign Spreads, Central Bank Collateral Frameworks, and Periphery Premia in the Eurozone. Dezernat Zukunft.

- Setser, Brad. 2025. “The Dollar’s Global Role and Financing the u.s. External Deficit.” Council on on Foreign Relations, June.

- Siemens Energy AG. 2025a. Annual Report 2025. Annual Report. Siemens Energy AG.

- Siemens Energy AG. 2025b. Q4 FY25 Analyst Presentation. Analyst Presentation. Siemens Energy AG.

- Sigl-Glöckner, Philippa. 2024. Gutes Geld. Quadriga.

- S&P Capital IQ. 2026. Key Stats and Multiples Reports: Magnificent Seven Companies. S&P Capital IQ Database.

- S&P Dow Jones Indices. 2026. S&p 500 Index, p/e Ratio (as Reported Earnings). Macrobond.

- Statistisches Bundesamt. 2025. “Außenhandel: Rangfolge Der Handelspartner Im Außenhandel.” Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis), October 2.

- Sultan, Samina, and Jürgen Matthes. 2025.

- Importabhängigkeit Der USA von Der EU: Eine Detaillierte Bestandsaufnahme. IW-Report 41/2025. Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft.

- Teer, Joris, Abe de Ruijter, and Michel Rademaker. 2024. Navigating the Great Game of Chokepoints: Assessing Geopolitical Risks and Advancing Dutch and European Strategic Indispensability in Digital Value Chains. Research Report. The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (HCSS).

- The Guardian. 2026. “Trump’s US Stranglehold on EU and UK Energy Supply Through LNG.” The Guardian, January 21.

- United States Congress, Joint Committee on Internal Revenue Taxation, United States Dept. of the Treasury and United States Congress Senate Committee on Finance. 1964. The Interest Equalization Tax Act of 1963 (h.r. 8000): Outline of Provisions of h.r. 8000, as Passed by the u.s. House of Representatives, and Amendments Recommended by the Treasury Department. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2026. “Trump Accounts: Jumpstarting the American Dream.” U.S. Department of the Treasury.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. 2025. Uranium Marketing Annual Report: With Data for 2024. Annual Report. U.S. Energy Information Administration.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2021. Federal Debt Management: Treasury Quickly Financed Historic Government Response to the Pandemic and Is Assessing Risks to Market Functioning. GAO Report GAO-21-606. U.S. Government Accountability Office.

- U.S. International Trade Commission. 2026. “DataWeb: U.s. Trade Statistics.” U.S. International Trade Commission.

- van ’t Klooster, Jens, Edoardo D. Martino, and Eric Monnet. 2025. Cryptomercantilism Vs. Monetary Sovereignty: Dealing with the Challenge of US Stablecoins for the EU. Study. European Parliament, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific; Quality of Life Policies.

- World Bank. 2024. “GDP (Current US$) – Russian Federation.”